Did you know the power of the US Congress to levy taxes has roots stretching back to 13th-century England? Peter Paccione’s article, “King, Parliament, and Taxation in English Constitutional History,” unravels the fascinating origins of the principle that the monarch cannot levy taxes without parliamentary consent. From Magna Carta to the conflicts of the Stuart period and the ultimate resolution in the 1689 Declaration of Rights, Paccione dissects how this fundamental right became enshrined in English constitutional law. If you’ve ever wondered about the historical bedrock of modern fiscal democracy, this is essential reading.

King, Parliament, and taxation in English constitutional history

The principle in English constitutional law that the king cannot levy taxation without the consent of Parliament was established in the thirteenth century. This principle is the origin of the power of Congress to levy taxes enumerated in Article 1 of the United States Constitution. This issue has again become relevant as in May 2025, the Court of International Trade ruled that the president does not have the “unbounded authority” to impose tariffs, citing Article 1 which assigned Congress the “exclusive powers” to ‘“lay Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises’ and to ‘regulate Commerce with foreign Nations.’” I would like to explore the origin of this principle of the English constitution.

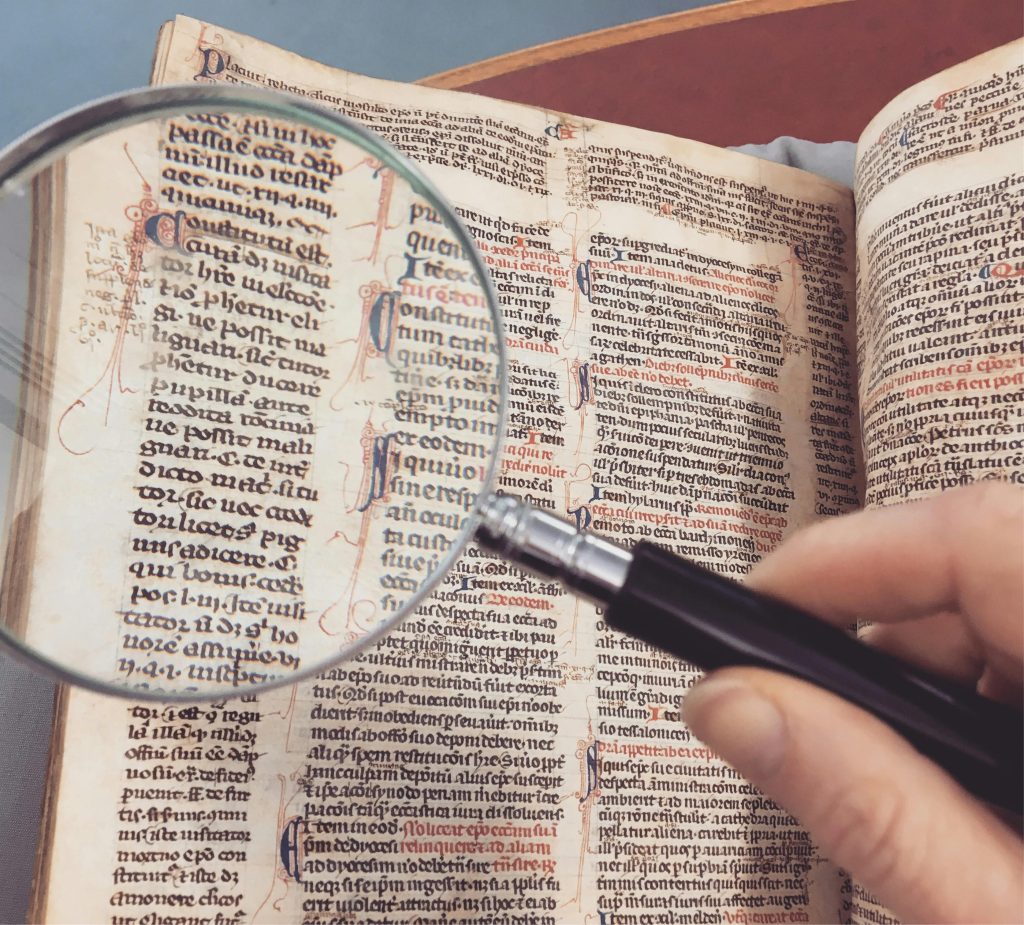

The principle that the king should levy non-feudal taxation only with the common consent of the realm could be traced back to chapters twelve and fourteen of Magna Carta, and it was during the thirteenth century that Parliament itself evolved from the council of magnates, or great council (magnum concilium), as the institution from which such consent was to be obtained.[1] Under Edward I, the crisis of the 1290s established that the monarchy could not levy taxation without the consent of Parliament. Beginning in 1294, parliaments were summoned for four consecutive years because of war with France and Scotland. The heavy war taxation was resented by many, and at a parliament in October 1297, the barons presented a list of demands, De Tallagio non concedendo, which included the levying of non-feudal taxation only with the common consent of the realm. At this parliament, Edward agreed to the Confirmation of the Charters (Confirmatio Cartarum), which confirmed Magna Carta and the Forest Charter, and promised that taxation would henceforth be levied with common consent.[2] The king promised that he would not take “such manner of aids, mises or prises” except “with the common assent of all the realm…”[3] J. R. Maddicott writes that the Confirmation “acknowledged that direct taxes could not be levied by the king’s will alone.”[4] It “entrenched parliament’s future role as a tax-granting assembly.”[5] In 1340, in response to the heavy taxation required by the Hundred Years War, Parliament demanded redress of grievances from Edward III before it agreed to any taxes. The Statute of 1340 stated that no future grant or charge would be levied “unless it be by the common assent of the earls, barons, and other great men and of the commons of our said realm of England, and that in parliament.”[6] According to B. Wilkinson, “Modern parliamentary control over the purse dates effectively from the Statute of 1340.”[7]

Parliamentary consent to taxation became a political issue in the early Stuart period. When James I became king in 1603, the government was in dire need of money and deep in debt, and when Parliament met in 1604 it was soon preoccupied with the financial crisis. The government looked for ways to raise revenue, and one source of income which James exploited was impositions, or customs duties. In the Bate’s case decision of 1606, the exchequer court upheld the king’s right to levy impositions without parliamentary consent. Taking advantage of this decision, the government announced in July 1608 new impositions on some 1400 items, which would yield about 70,000 pounds a year.[8] Impositions became a major issue in the parliamentary session of 1610. In the House of Commons on June 28, Nicholas Fuller spelled out the basic objection to impositions, that they were levied without parliamentary consent and were thus illegal and a threat to English liberties. Fuller cited cases from English history in which the monarchy had recalled impositions because they did not have parliamentary consent.[9] He cited the Confirmation of the Charters, De Tallagio non concedendo, and the statute of 1340 as evidence that the monarchy did not have the right to tax without parliamentary consent.[10] On June 28, William Hakewill spoke of the danger to the constitution which impositions presented. The king, he said, could not levy taxes or impositions without the consent of Parliament. “If it were otherwise, you see how it were to the utter dissolution and destruction of that politic frame and constitution of this commonwealth which I have opened unto you…”[11] Hakewill cited Magna Carta, the Tallagio, the Confirmation, and the statute of 1340 in which the king promised not to tax without parliamentary consent.[12] He said of the four acts that “I affirm that so stands the law of England at this day, by reason of statutes directly in the point, as the king’s power, if ever he had any, to impose, is not only limited, but utterly taken away…”[13] Thomas Hedley then asserted that impositions were a violation of the principle of common law that the king cannot tax without parliamentary consent.[14] On July 2, James Whitelocke said, “Besides this right of imposing, there be others in the kingdom of the same nature: as the power to make laws…all which do belong to the King only in Parliament.”[15]

In 1634, Charles I and his council decided upon ship money as a way of financing naval expansion. In October, the first ship money writs were sent to coastal counties and localities, requiring them to contribute either ships or money to the navy. The purposes of the naval expansion were the defense of the kingdom from invasion, the protection of merchant shipping, and the fighting of piracy. The government considered ship money not as a tax but as a service. In August 1635, a second writ extended ship money to the entire country.[16] From the beginning, ship money encountered resistance and objections on constitutional grounds as unparliamentary taxation. When the Short Parliament assembled in April 1640, it ignored the king’s request for money and insisted on the airing of grievances before supply, grievances which included financial expedients such as ship money and knighthood and forest fines.[17] On April 30, during a Commons debate on ship money, Alexander Rigby cited Magna Carta, De Tallagio non concedendo, the statute of 1340, and the Petition of Right of 1628 as evidence that ship money was illegal, quoting the statute of 1340 as saying, “no aid, charge or other such thing shall be levied of the subject but by act of parliament.” He was followed by George Peard, who cited the Tallagio and the Confirmation of the Charters of 1297.[18]

When the Long Parliament met in December 1640, it was determined to dismantle the Stuart system of arbitrary government and abolished many of the Stuart financial expedients and other institutions of royal tyranny. In June 1641, customs duties including impositions and tonnage and poundage were made illegal without parliamentary consent, and in August, ship money, forest fines and knighthood fines were abolished. All of these expedients had been used at one time or another by James I and Charles I, and Parliament had decided that no future king would have them at their disposal.[19] Alan Cromartie calls the constitutional reforms of the first nine months of the Long Parliament the “final victory of English common law as the criterion of authority: a constitutionalist revolution.”[20] The issue of taxation without parliamentary consent was finally resolved by article 4 of the Declaration of Rights of 1689: “That levying of money for or to the use of the crown by pretense of prerogative without grant of Parliament for longer time or in other manner than the same is or shall be granted is illegal.” This was a confirmation of an ancient right of Parliament and was a final settlement of an issue that had been the cause of constitutional conflict since the beginning of the Stuart period.[21]

The members of Parliament who spoke against taxation without parliamentary consent identified the continuing existence of Parliament with the existence of the rights and liberties of the English, rights and liberties which had originated or had been confirmed during the medieval period. One of these rights was the common consent of the realm to taxation. The principle that taxation could not be levied without parliamentary consent was fundamental to the English constitution; it was the principle from which all other rights and privileges of Parliament originated.

References:

[1] G. L. Harriss, King, Parliament and Public Finance in Medieval England to 1369 (Oxford, 1975), 27.

[2] J. R. Maddicott, The Origins of the English Parliament, 924-1327 (Oxford, 2010), 302-303.

[3] Harry Rothwell, ed., English Historical Documents. vol. 3 (New York, 1975), 486.

[4] Maddicott, The Origins of the English Parliament, 307.

[5] Ibid., 308.

[6] B. Wilkinson, The Constitutional History of Medieval England, v. 3 (London, 1958), 365-366.

[7] Ibid., v. 3, 338.

[8] Mark Kishlansky, A Monarchy Transformed: Britain 1603-1714 (London, 1996), 85-86.

[9] Wallace Notestein, The House of Commons 1604-1610 (New Haven, 1971), 362.

[10] Elizabeth Read Foster, ed., Proceedings in Parliament 1610, vol. 2 (New Haven, 1966), 162.

[11] J. R. Tanner, Constitutional Documents of the Reign of James I, 1603-1625 (Cambridge, 1960), 253.

[12] Notestein, House of Commons, 372-373.

[13] T. B. Howell, ed., A Complete Collection of State Trials, vol. 2 (Buffalo, 2000), 455.

[14] Foster, Proceedings in Parliament 1610, vol. 2, 188-189.

[15] Tanner, Constitutional Documents of the Reign of James I, 260-261.

[16] Kevin Sharpe, The Personal Rule of Charles I (New Haven, 1992), 545-558.

[17] Richard Cust, Charles I: A Political Life (Harlow, UK, 2005), 252-254.

[18] Judith D. Maltby, ed., The Short Parliament (1640) Diary of Sir Thomas Aston, Camden Society fourth series, 35 (London, 1988), 101-102.

[19] David L. Smith, The Stuart Parliaments, 1603-1689 (London, 1999), 124.

[20] Alan Cromartie, The constitutionalist revolution: an essay on the history of England, 1450-1642 (Cambridge, 2006), 261.

[21] Lois Schwoerer, The Declaration of Rights, 1689 (Baltimore, 1981), 66-69.

Author: