Though Nazi Germany is widely studied, the instrumental role of popular culture in its propaganda machine is sometimes overlooked. In “Popular Culture, Propaganda, and Activism in Nazi Germany: Mechanisms of Indoctrination and Control,” Dylan Aunger analyzes how film, literature, music, art, and radio were used to disseminate propaganda and enforce ideological conformity. His work illuminates the ways the regime embedded its ideology in everyday life through cultural mediums.

Popular Culture, Propaganda, and Activism in Nazi Germany: Mechanisms of Indoctrination and Control

The relationship between popular culture, propaganda, and activism in Nazi Germany was intricate and functioned as a fundamental instrument in shaping public opinion, enforcing ideological conformity, and legitimising the policies of the regime. Popular culture, comprising film, literature, music, art, and mass media, became a crucial arena through which Nazi propaganda infiltrated daily life, shaping both conscious and subconscious attitudes towards the regime’s vision for Germany. This article explores how the Nazi state harnessed popular culture to disseminate propaganda and activate support for its political objectives, while also engaging with historiographical debates around the reception and impact of this propaganda.

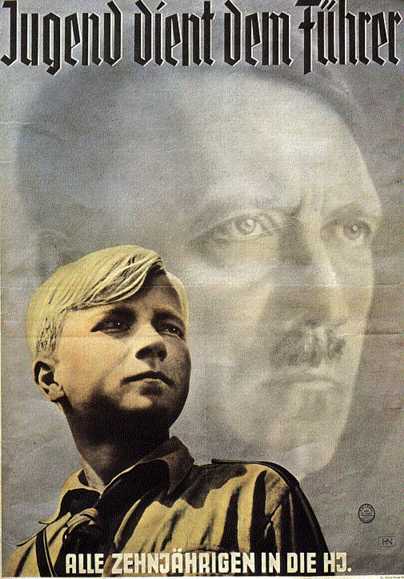

Nazi propaganda, under the direction of Joseph Goebbels and the Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, was central to the regime’s efforts to consolidate power and promote ideological homogeneity. Scholars such as Ian Kershaw argue that the propaganda machine was essential in creating the “Hitler Myth,” portraying the Führer as the embodiment of the German people’s will and aspirations.[1] In contrast, historians like David Welch suggest that the effectiveness of Nazi propaganda was not uniform and often depended on pre-existing societal attitudes.[2] Nonetheless, there is consensus that propaganda was instrumental in reinforcing Nazi racial doctrines and nationalistic fervor.

Film was perhaps the most potent tool in the Nazi propaganda arsenal. Heavily censored and regulated by the state, cinema was used to glorify Hitler, depict Jews and other minorities as threats, and promote the heroic image of the Aryan race. Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will (1935) is often cited as a paradigmatic example of this visual propaganda. The film presents the 1934 Nuremberg Rally in stylised grandeur, reinforcing the myth of unity, power, and the divine authority of Hitler.[3] Despite debates over Riefenstahl’s personal motivations and artistic autonomy, her work undeniably served as a compelling medium of Nazi ideology.

Literature also played a key role in shaping the ideological framework of the Third Reich. Books approved by the regime romanticised the Nazi vision and propagated racial purity. Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf served as the ideological bedrock of Nazism, outlining his virulently anti-Semitic and expansionist worldview.[4] Other authors, such as Alfred Rosenberg and Joseph Goebbels, contributed to the literary dissemination of Nazi ideals. Historians such as Richard J. Evans highlight how literature was utilised in schools and public libraries to indoctrinate the youth, making Nazi ideology part of the intellectual fabric of society.[5]

Music and festivals became conduits for emotional mobilisation. Songs extolling Hitler and celebrating German nationalism were widely distributed and performed at rallies, schools, and festivals. The Hitler Youth and League of German Girls used musical activities as part of their indoctrination strategies.[6] Patriotic songs, often with catchy melodies and nationalist lyrics, helped forge emotional bonds between individuals and the regime, embedding ideology within the cultural memory of the population. Historian Michael Kater explores the dual role of music as both entertainment and political instrument, arguing that musical propaganda was effective in normalising the Nazi worldview.[7]

Art and visual culture were similarly marshalled in the service of ideology. The Nazis promoted art that adhered to classical forms and celebrated Aryan physicality, traditional gender roles, and Germanic heritage. The regime simultaneously denounced and suppressed so-called “degenerate art,” which included modernist, abstract, and expressionist works, particularly those by Jewish or politically subversive artists. The 1937 “Degenerate Art” exhibition in Munich, which aimed to ridicule non-conforming art, exemplifies the regime’s use of visual culture to enforce aesthetic and ideological norms.[8]

Radio was another critical vehicle for propaganda. The regime ensured widespread access to affordable radios (Volksempfänger), which became ubiquitous in German households. Through radio broadcasts, speeches by Hitler and other high-ranking officials were transmitted directly into homes, allowing the regime to saturate the public sphere with its message.[9] Scholars such as Eric Rentschler emphasise that radio created a shared auditory experience that reinforced collective identity and national unity.[10]

The relationship between propaganda and activism in Nazi Germany was not merely top-down; rather, propaganda fostered conditions conducive to active participation in Nazi goals. Organisations like the Hitler Youth and the League of German Girls did not merely indoctrinate; they activated ideological loyalty through structured activities, rallies, and public service.[11] Mass rallies and parades served as orchestrated performances of power and unity, visually and emotionally affirming Nazi supremacy.

Historiographical debate persists regarding the extent to which propaganda genuinely converted the German population versus reinforcing existing beliefs. Some historians argue that propaganda acted more as a means of affirming consensus among the already sympathetic rather than converting the sceptical.[12] Others suggest that propaganda contributed to a climate of fear and conformity, where even those who doubted the regime felt compelled to comply publicly.[13]

Resistance to propaganda, while limited, did exist. Underground publications, such as those by the White Rose group, and clandestine listening to foreign radio broadcasts reveal that not all Germans were passive recipients of Nazi ideology.[14] However, such dissent was dangerous and relatively rare, underscoring the pervasive reach of the propaganda state.

In conclusion, the use of popular culture in Nazi Germany was a deliberate and strategic effort to infuse every aspect of life with ideological content. Through film, literature, music, art, and radio, the regime succeeded in embedding its vision within the social fabric of the nation. Propaganda did not merely transmit information; it structured perception, reinforced activism, and reshaped public consciousness. The historical debates around its effectiveness highlight the complex interplay between state influence and individual agency, reminding us of the enduring power of cultural mediums in shaping political reality.

References:

[1] Ian Kershaw, The “Hitler Myth”: Image and Reality in the Third Reich (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987), pp. 4–6.

[2] David Welch, The Third Reich: Politics and Propaganda (London: Routledge, 2002), pp .19–21.

[3] Susan Sontag, “Fascinating Fascism,” in Under the Sign of Saturn (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1980), pp. 73–105

[4] Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf, trans. Ralph Manheim (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1999)

[5] Richard J. Evans, The Third Reich in Power (London: Penguin Books, 2005), pp. 123–125

[6] Lisa Pine, Education in Nazi Germany (Oxford: Berg, 2010), pp. 52–5

[7] Michael H. Kater, Different Drummers: Jazz in the Culture of Nazi Germany (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992), pp. 45–49

[8] Stephanie Barron, ed., “Degenerate Art”: The Fate of the Avant-Garde in Nazi Germany (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1991), pp. 12–16

[9] Horst J.P. Bergmeier and Rainer E. Lotz, Hitler’s Airwaves: The Inside Story of Nazi Radio Broadcasting and Propaganda Swing (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997), pp. 24–28

[10] Eric Rentschler, The Ministry of Illusion: Nazi Cinema and Its Afterlife (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996), pp. 63–65

[11] Michael H. Kater, Hitler Youth (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004), pp. 89–93

[12] Welch, The Third Reich, p. 112

[13] Evans, The Third Reich in Power, pp. 87–90

[14] Annette Dumbach and Jud Newborn, Sophie Scholl and the White Rose (Oxford: Oneworld, 2006), pp. 36–39

Author