“Discover significant historical events that happened on this day, from ancient times to the modern era.”

Latest ‘On these Day in History’ entries for the past month:

On This Day in History: October 16, 1793 – Marie Antoinette Executed

On This Day in History: October 16, 1793 – Marie Antoinette Executed

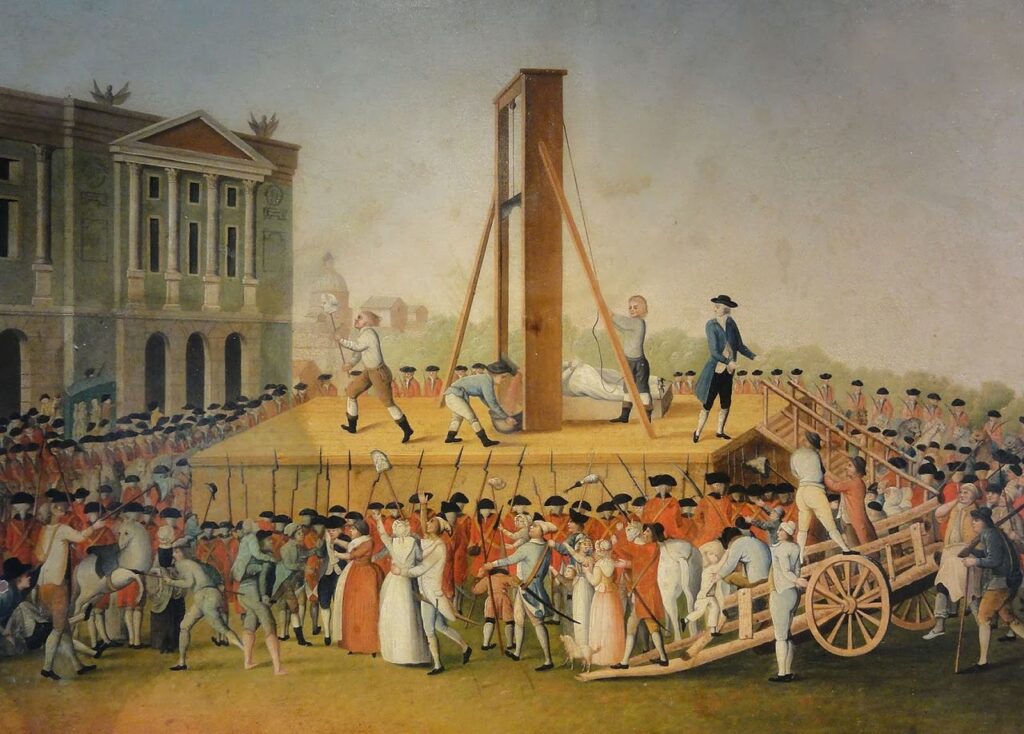

On October 16, 1793, the Place de la Révolution in Paris echoed with the thud of the guillotine as Marie Antoinette, the last queen of France, met her end at age 37. The former archduchess of Austria, once a symbol of opulent excess, was led through jeering crowds to the scaffold, her hair cropped short and hands bound. This execution, the culmination of a sham trial amid the Reign of Terror, not only sealed the fate of the French monarchy but also exposed the Revolution’s descent into vengeance, misogyny, and political theater. Marie Antoinette’s death marked a grim turning point, amplifying global debates on power, gender, and justice.

Born Maria Antonia in 1755 to Holy Roman Empress Maria Theresa, she married the future Louis XVI in 1770 at age 14, sealing an alliance against British expansion. Her early years at Versailles were defined by lavish spending—rumored “Let them eat cake” epitomizing her detachment from the starving masses. The French Revolution, sparked by financial crisis and Enlightenment ideals, turned public fury on her. After the storming of the Bastille in 1789, she became the Revolution’s scapegoat: “Madame Deficit,” a foreign plotter undermining France. Louis XVI’s execution in January 1793 left her a widow, imprisoned in the Conciergerie, and subjected to brutal interrogations.

Her trial, beginning October 14 before the Revolutionary Tribunal, was a farce. Accused of treason, depleting the treasury, and incest with her son (a charge rooted in misogynistic propaganda), she defended herself with dignity, famously silencing accusers by declaring a mother incapable of such acts. Condemned without appeal, she faced the guillotine dressed in white, her final words to the executioner: “Pardon me, sir. I meant not to do it.” The blade fell at noon, her body dumped in an unmarked grave—later exhumed for a 1815 reburial.

The execution’s impact was seismic. It radicalized the Revolution, fueling the Terror’s 40,000 deaths, but also sowed its downfall, as public revulsion grew. Globally, it horrified monarchies, strengthening coalitions against France, while inspiring radicals. In Ireland, under British rule, Marie Antoinette’s fate resonated with Catholic nationalists; the United Irishmen, influenced by the Revolution, saw her as a martyr against tyranny, paralleling their own struggles. Gender dynamics were stark: her trial weaponized femininity, portraying her as a sexual threat, a trope that echoed in later political scapegoating of women.

Marie Antoinette’s death was more than a royal tragedy; it was a mirror to the Revolution’s ideals and excesses. She embodied both frivolity and fortitude, her story immortalized in works like Let Them Eat Cake and Sofia Coppola’s film. On October 16, 1793, the guillotine silenced a queen, but her legacy endures as a cautionary tale of power’s fragility and the human cost of radical change.

Published by The Uncharted Past Team

On This Day in History: October 15, 1066 – Harold Godwinson Crowned King of England

On This Day in History: October 15, 1066 – Harold Godwinson Crowned King of England

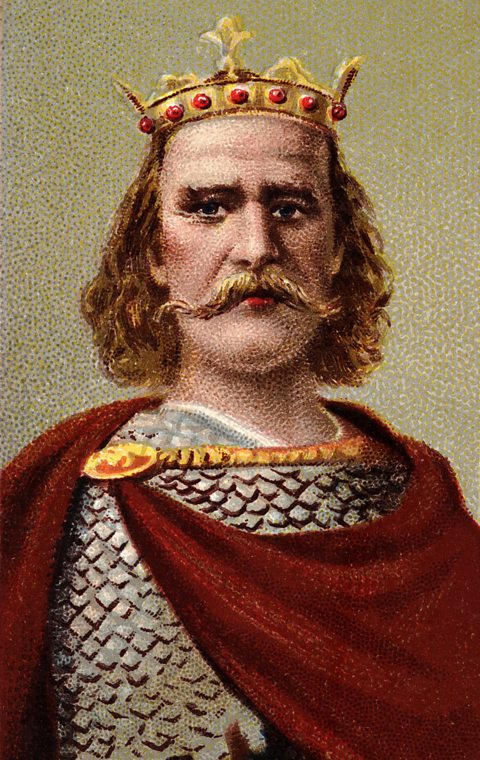

On October 15, 1066, Westminster Abbey resounded with the solemn rites as Harold Godwinson was crowned King of England, ascending the throne in a moment of profound uncertainty. This coronation, just three days after Edward the Confessor’s death, ignited a succession crisis that culminated in the Norman Conquest. Harold’s brief reign, marked by rapid challenges from Norway and Normandy, reshaped English history, influencing political structures, language, and Ireland’s ties to England.

Harold, a powerful Anglo-Saxon earl of Wessex, had been Edward’s favored successor, supported by the Witan (noble council). Edward’s death on January 5 left no heir, and Harold was swiftly elected and crowned. His ascension was controversial: Harald Hardrada of Norway claimed the throne via a pact with Harthacnut, and William, Duke of Normandy, asserted a promise from Edward. Harold’s coronation, officiated by Archbishop Stigand, symbolized continuity of Anglo-Saxon rule but was seen by rivals as usurpation.

Harold’s reign was a whirlwind of defense. On September 25, he defeated Hardrada at Stamford Bridge, only to face William’s invasion on October 14 at Hastings. Harold’s death in battle ended Anglo-Saxon monarchy, ushering in Norman rule. William’s conquest centralized power, introducing feudalism and French influence, transforming English law and culture.

The event’s impact was far-reaching. The Norman Conquest fused Anglo-Saxon and Norman traditions, enriching English language and governance. In Ireland, Harold’s defeat facilitated Norman invasions from 1169, leading to English lordship over Ireland by 1171. Socially, it displaced Anglo-Saxon elites, though many adapted, blending cultures. Gender roles shifted minimally, but Norman women gained property rights under feudal law.

Globally, Hastings exemplified the era’s power struggles, influencing medieval Europe’s feudal systems. In Ireland, the conquest’s legacy fueled resistance against English rule, from the 13th-century Gaelic revival to modern independence.

On October 15, 1066, Harold Godwinson’s coronation heralded a fleeting Anglo-Saxon revival, swiftly eclipsed by conquest. It was a moment of hope and hubris, forging a new England from the ashes of the old. Today, we reflect on this turning point, honoring the resilience of those who navigated its turbulent wake.

Published by The Uncharted Past Team

On This Day in History: October 14, 1964 – Martin Luther King Jr. Wins Nobel Peace Prize

On This Day in History: October 14, 1964 – Martin Luther King Jr. Wins Nobel Peace Prize

On October 14, 1964, a beacon of hope shone brightly as the Norwegian Nobel Committee announced that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the 35-year-old American civil rights leader, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his nonviolent campaign against racial injustice. This prestigious recognition, bestowed in Oslo, celebrated King’s leadership in the U.S. Civil Rights Movement, affirming his global influence and galvanizing the fight for equality. The award not only honored a transformative figure but also amplified the struggle for justice, resonating far beyond America, including in Ireland’s own civil rights struggles.

King, a Baptist minister and head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, led the movement to dismantle segregation and secure voting rights for African Americans. His philosophy of nonviolent resistance, inspired by Mahatma Gandhi, was showcased in landmark events like the 1963 March on Washington, where his “I Have a Dream” speech captivated the world. The Nobel Committee praised King for his “firm conviction that nonviolence is the most powerful weapon available to oppressed people,” noting his role in uniting millions against systemic racism. At the time, he was the youngest Nobel Peace Prize recipient, accepting the award in Oslo on December 10, 1964, and donating the $54,123 prize to civil rights organizations.

The award had profound impacts. It bolstered the Civil Rights Movement, strengthening momentum for the 1964 Civil Rights Act and 1965 Voting Rights Act, which outlawed segregation and protected Black voting rights. Globally, it inspired liberation movements, from South Africa’s anti-apartheid struggle to Ireland’s civil rights campaigns in Northern Ireland, where activists like John Hume drew parallels with their fight against discrimination. Socially, King’s recognition elevated African-American voices and highlighted women’s roles in the movement, such as Rosa Parks and Coretta Scott King, though gender equality within activism remained a challenge.

In Ireland, the award resonated deeply, as the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association, formed in 1967, echoed King’s nonviolent tactics to address Catholic disenfranchisement. The global spotlight on King also intensified scrutiny of racial and social injustices, influencing international human rights frameworks. His assassination in 1968 only amplified his martyrdom, cementing his legacy as a symbol of courage and moral clarity.

On October 14, 1964, Martin Luther King Jr.’s Nobel Peace Prize illuminated the power of nonviolence in the face of oppression. It was a moment of triumph and inspiration, uniting people across borders in the pursuit of justice. Today, we honor King’s legacy, reflecting on the enduring call to fight inequality with compassion and resolve.

Published by The Uncharted Past Team

On This Day in History: October 13, 54 – Nero Becomes Roman Emperor

On This Day in History: October 13, 54 – Nero Becomes Roman Emperor

On October 13, 54, the Roman Empire entered a new and controversial chapter as Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, only 16 years old, was proclaimed emperor following the death of his adoptive father, Claudius. Nero’s ascension in Rome marked the beginning of a reign that would oscillate between cultural patronage and notorious tyranny, leaving a complex legacy that shaped the empire’s trajectory and resonated through history. His rule, marked by extravagance, brutality, and the Great Fire of Rome, became a defining moment in the Julio-Claudian dynasty.

Nero, born in 37 in Antium, was the son of Agrippina the Younger and Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus. Adopted by Claudius at Agrippina’s urging, he was groomed for power, tutored by the philosopher Seneca. Claudius’s death—possibly by poisoning orchestrated by Agrippina—elevated Nero to the throne, bypassing Claudius’s biological son, Britannicus. On October 13, the Praetorian Guard, influenced by Agrippina and prefect Burrus, declared Nero emperor, and the Senate swiftly confirmed him. His early reign, guided by Seneca and Burrus, was marked by relative stability, with reforms to curb corruption and lavish public entertainments, including chariot races and theatrical performances.

However, Nero’s rule soon descended into infamy. His passion for the arts—performing as a poet and musician—scandalized Roman elites, who deemed such acts unbecoming of an emperor. The Great Fire of 64, which devastated Rome, led to rumors that Nero fiddled while the city burned, though he likely helped organize relief efforts. His subsequent persecution of Christians, blamed for the fire, and executions of rivals, including Britannicus and Agrippina, cemented his reputation for cruelty. By 68, revolts and Senate opposition forced Nero to flee, leading to his suicide at age 30, ending the Julio-Claudian line.

Nero’s reign had lasting impacts. His rebuilding of Rome, including the opulent Golden House, strained finances but advanced urban planning. His policies influenced early Christian martyrdom narratives, shaping religious history. In Ireland, distant from Rome, Nero’s persecution of Christians resonated later with the island’s Christian communities, established by the 5th century. Globally, Nero’s rule highlighted the dangers of unchecked power, influencing governance debates in later empires.

On October 13, 54, Nero’s rise to emperor ushered in an era of splendor and terror. It was a moment that tested the Roman Empire’s resilience, leaving a legacy of art, tyranny, and tragedy. Today, we reflect on Nero’s complex reign, a reminder of the delicate balance between leadership and excess in shaping history.

Published by The Uncharted Past Team

On This Day in History: October 12, 1928 – The First Iron Lung Used

On This Day in History: October 12, 1928 – The First Iron Lung Used

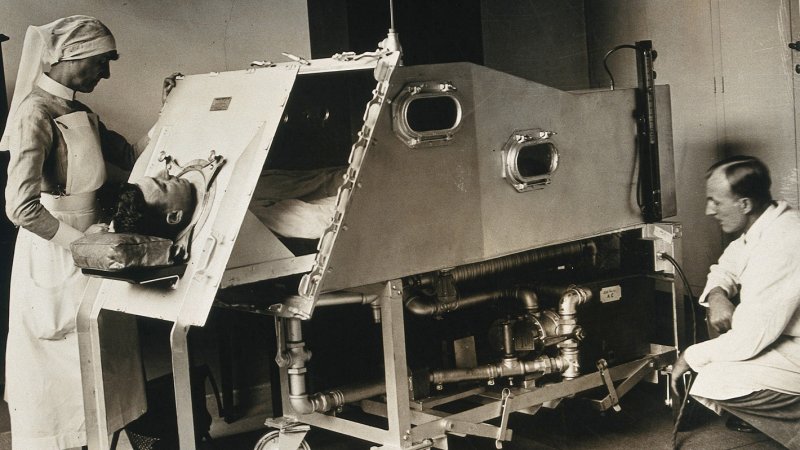

On October 12, 1928, a groundbreaking moment in medical history unfolded at Boston’s Children’s Hospital when the first iron lung was used to save the life of an eight-year-old girl suffering from polio-induced respiratory paralysis. This innovative device, developed by Harvard engineers Philip Drinker and Louis Agassiz Shaw, marked a technological triumph that revolutionized treatment for polio patients, offering hope during a devastating epidemic. The iron lung’s debut not only transformed medical care but also highlighted the intersection of science, compassion, and societal resilience, with echoes felt globally, including in Ireland.

Polio, a highly contagious viral disease, was a global scourge in the early 20th century, paralyzing thousands annually, particularly children. By the 1920s, severe cases led to respiratory failure, with no effective treatment. The iron lung, a negative-pressure ventilator, encased a patient’s body in a sealed chamber, using air pressure changes to mimic breathing. On October 12, the device was first used to sustain the young patient, who survived her acute crisis, demonstrating its life-saving potential. The machine’s success spurred widespread adoption in hospitals, becoming a symbol of hope during polio outbreaks until vaccines emerged in the 1950s.

The iron lung’s impact was profound. It enabled thousands to survive polio’s worst effects, with patients, often children, living inside the machines for weeks or years. Socially, it highlighted the resilience of those afflicted, many of whom, including women, adapted to life with disability, inspiring advocacy for accessibility. In Ireland, where polio epidemics struck in the 1940s and 1950s, iron lungs were used in hospitals like Dublin’s Dr. Steevens’ Hospital, galvanizing public health efforts and vaccine campaigns. The device also spurred medical innovation, influencing modern ventilators used in intensive care.

Globally, the iron lung became a cultural icon, appearing in media and symbolizing human ingenuity against disease. Its development reflected collaborative efforts, with nurses—often women—playing critical roles in patient care, advancing gender visibility in healthcare. However, the machines were costly, highlighting disparities in access, a concern in Ireland’s strained post-war health system. The iron lung’s legacy endures in respiratory medicine and polio survivor stories, shaping disability rights movements.

On October 12, 1928, the first use of the iron lung marked a beacon of hope in the fight against polio. It was a moment of scientific triumph and human perseverance, saving lives and inspiring progress. Today, we honor this milestone, reflecting on its legacy in medical innovation and the enduring strength of those who faced adversity with courage.

Published by The Uncharted Past Team

On This Day in History: October 11, 1986 – The Reagan-Gorbachev Reykjavik Summit

On This Day in History: October 11, 1986 – The Reagan-Gorbachev Reykjavik Summit

On October 11, 1986, the windswept capital of Iceland, Reykjavik, became the stage for a historic Cold War summit between U.S. President Ronald Reagan and Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev. This two-day meeting, intended as a preliminary discussion, unexpectedly brought the world tantalizingly close to abolishing nuclear arsenals. Though it ended without an agreement, the Reykjavik Summit marked a pivotal moment in U.S.-Soviet relations, laying the groundwork for future arms control and the eventual end of the Cold War, resonating globally, including in neutral Ireland.

The summit followed years of heightened tensions, with both superpowers amassing vast nuclear stockpiles. Reagan, a staunch anti-communist, pushed his Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), a missile defense system, while Gorbachev, seeking economic reform through perestroika and glasnost, aimed to reduce military burdens. Meeting at Höfði House, the leaders proposed drastic cuts to nuclear weapons, with Gorbachev suggesting a 50% reduction and Reagan countering with a vision to eliminate all nuclear missiles within a decade. The talks, initially informal, grew intense, with both sides nearing a historic deal to eliminate intermediate-range missiles and potentially all nuclear weapons.

The summit faltered over SDI. Gorbachev demanded its restriction to laboratory research, fearing it could destabilize deterrence, while Reagan refused to abandon the program, viewing it as a defensive necessity. Despite the impasse, the talks were a breakthrough, fostering trust and leading to the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, which eliminated an entire class of missiles. The summit’s candid discussions also humanized U.S.-Soviet relations, setting the stage for further détente and the Soviet Union’s eventual dissolution in 1991.

Globally, Reykjavik was a beacon of hope, signaling that nuclear disarmament was possible. In Ireland, a neutral nation with a strong anti-nuclear stance, the summit was closely followed, aligning with campaigns like the Irish Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, which drew inspiration from global peace efforts. Socially, the talks highlighted the role of diplomacy in averting catastrophe, influencing public opinion and empowering peace movements, including those led by women, who were active in anti-nuclear protests worldwide.

On October 11, 1986, the Reykjavik Summit brought the world to the brink of a nuclear-free future, only to fall short, yet it ignited hope for peace. It was a moment of bold vision and compromise, reshaping global security. Today, we honor Reagan and Gorbachev’s courage to negotiate, reflecting on the power of dialogue to steer humanity away from destruction.

Published by The Uncharted Past Team

On This Day in History: October 10, 1780 – The Great Hurricane of 1780 Begins

On This Day in History: October 10, 1780 – The Great Hurricane of 1780 Begins

On October 10, 1780, the Caribbean was struck by a cataclysmic force of nature known as the Great Hurricane of 1780, the deadliest Atlantic hurricane in recorded history. Ravaging islands from Barbados to Bermuda over several days, this catastrophic storm killed an estimated 20,000–27,500 people, devastated economies, and disrupted colonial powers during the American Revolutionary War. The hurricane’s wrath not only reshaped communities but also highlighted the vulnerability of societies to natural disasters, leaving a somber legacy in the Caribbean and beyond.

The storm, likely a Category 5 hurricane with winds exceeding 200 mph, began its destructive path on October 10, hitting Barbados with unprecedented fury. It leveled homes, uprooted trees, and sank ships, killing thousands. Moving northwest, it struck Martinique, St. Lucia, and St. Eustatius, destroying plantations, fortifications, and entire towns. In Martinique, 9,000 perished, while St. Eustatius lost nearly all its buildings. The hurricane’s toll included enslaved Africans, European settlers, and soldiers, with naval losses impacting British, French, and Dutch fleets engaged in the Revolutionary War. The British lost 40 ships, and the French navy suffered heavily, weakening their regional operations.

The social and economic impacts were profound. The hurricane decimated the Caribbean’s plantation economies, reliant on sugar and slave labor, exacerbating food shortages and displacing thousands. Enslaved populations, already oppressed, faced heightened suffering, with little aid recorded. The disaster exposed colonial vulnerabilities, as relief efforts were slow and inadequate. In Ireland, a British colony, the hurricane’s effects were felt indirectly through disrupted trade and the involvement of Irish soldiers in Caribbean garrisons, stirring debates about colonial governance. Globally, the storm shifted military strategies, as weakened navies altered Revolutionary War dynamics, indirectly aiding American independence.

The Great Hurricane spurred early discussions on disaster preparedness, though systematic responses emerged later. It also left cultural scars, with survivor accounts shaping Caribbean folklore and resilience narratives. In the absence of modern meteorology, the storm’s unpredictability underscored humanity’s powerlessness against nature, a lesson that resonated in later centuries with events like Hurricane Katrina.

On October 10, 1780, the Great Hurricane of 1780 unleashed unparalleled destruction, forever altering the Caribbean’s social and economic fabric. It was a moment of tragedy and resilience, reminding us of nature’s indiscriminate power. Today, we honor the memory of those lost and reflect on the enduring need for preparedness and compassion in the face of natural disasters.

Published by The Uncharted Past Team

On This Day in History: October 9, 1967 – Che Guevara Executed

On This Day in History: October 9, 1967 – Che Guevara Executed

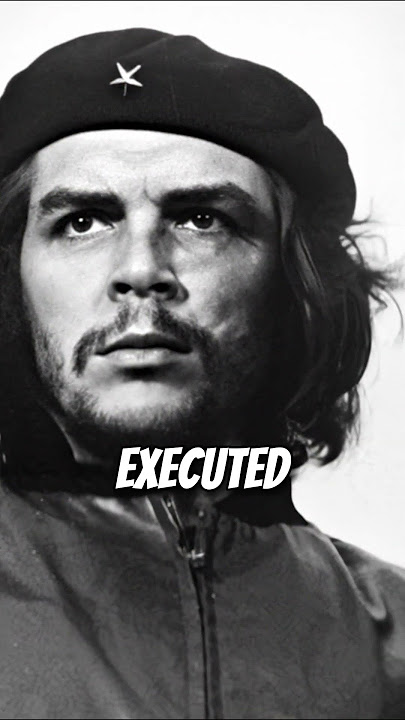

On October 9, 1967, Ernesto “Che” Guevara, the iconic revolutionary and symbol of global rebellion, was executed by Bolivian forces in La Higuera, Bolivia, with CIA assistance. Captured the previous day after a failed guerrilla campaign, Guevara’s death at age 39 marked the end of a charismatic figure whose image became a worldwide emblem of resistance. This event, set against the Cold War’s ideological battles, not only ended Guevara’s revolutionary efforts but also cemented his martyrdom, profoundly influencing political movements, culture, and global perceptions of defiance.

Born in Argentina in 1928, Guevara became a key figure in the 1959 Cuban Revolution alongside Fidel Castro, serving as a minister and advocate for socialist reforms. His vision of spreading revolution across Latin America led him to Bolivia in 1966, where he aimed to ignite a peasant uprising against the military government. Hampered by logistical failures, lack of local support, and U.S.-trained Bolivian forces, his small guerrilla band was tracked down. On October 8, Guevara was wounded and captured in a ravine. The next day, after brief interrogation, he was shot by Bolivian sergeant Mario Terán, reportedly on orders relayed through the CIA, which sought to crush communist insurgencies.

The execution had immediate and far-reaching impacts. In Bolivia, it quelled the insurgency but fueled anti-government sentiment. Globally, Guevara’s death transformed him into a martyr, his beret-clad image immortalized on posters and T-shirts, symbolizing resistance to imperialism. In Ireland, where revolutionary ideals resonated due to its own history of rebellion, Guevara’s death inspired activists during the Troubles, with murals in Belfast echoing his defiance. Socially, his legacy empowered youth and marginalized groups, including women in revolutionary movements, though his tactics sparked debate over violence versus diplomacy.

The event intensified Cold War tensions, as Latin American revolutions faced increased U.S. intervention. Guevara’s writings, like Guerrilla Warfare, continued to inspire movements from Africa to Asia, while his romanticized image shaped pop culture, from music to art. However, critics highlighted his role in Cuba’s repressive policies, complicating his legacy.

On October 9, 1967, Che Guevara’s execution marked the fall of a revolutionary but the rise of a global icon. It was a moment of tragedy and inspiration, reflecting the power of ideas to transcend death. Today, we honor Guevara’s complex legacy, reflecting on the enduring struggle for justice and the costs of revolutionary zeal.

Published by The Uncharted Past Team

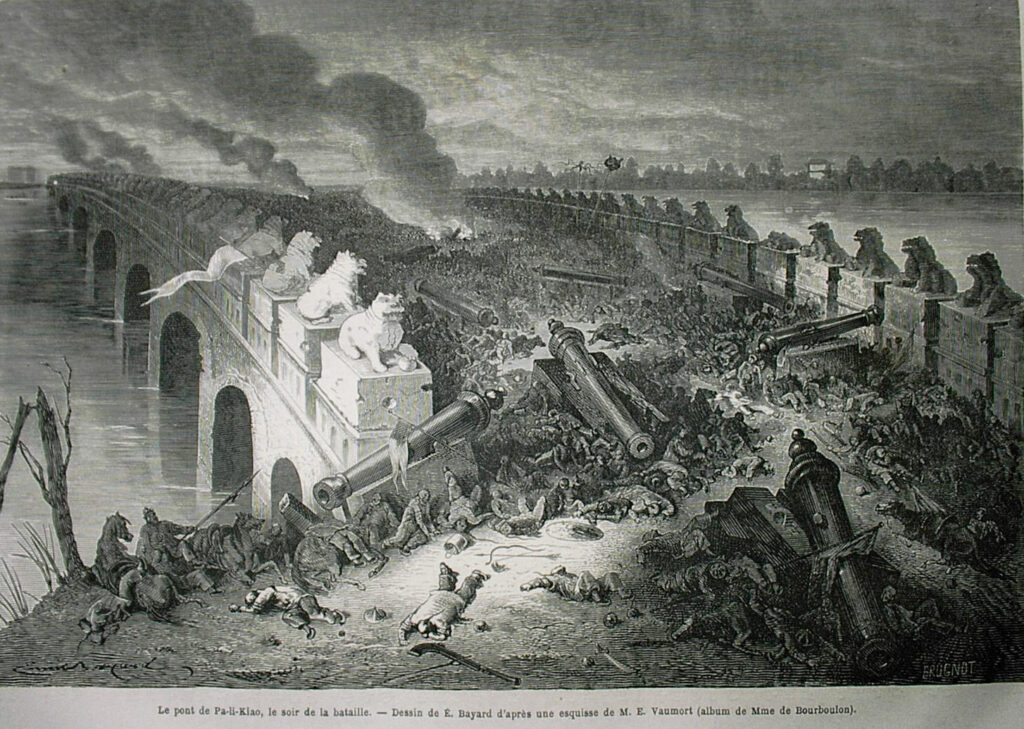

On This Day in History: October 8, 1856 – The Second Opium War Begins

On This Day in History: October 8, 1856 – The Second Opium War Begins

On October 8, 1856, the spark of conflict ignited in southern China when Qing authorities seized the British-registered ship Arrow in Canton (modern Guangzhou), marking the start of the Second Opium War. This clash between Britain, later joined by France, and the Qing dynasty escalated tensions over trade, diplomacy, and imperial ambitions, reshaping China’s relationship with the West. The war, rooted in colonial greed and cultural misunderstandings, not only humiliated China but also set the stage for its “century of humiliation,” with lasting global and social consequences.

The Arrow incident involved Qing officials boarding the ship, suspected of piracy and smuggling, and arresting its Chinese crew, prompting outrage from British authorities. Britain, eager to expand trade privileges gained in the First Opium War (1839–1842), used the seizure as a pretext to demand broader access to Chinese markets, including opium exports from British India. When Qing governor Ye Mingchen refused concessions, British forces bombarded Canton, initiating hostilities. France joined in 1857, citing the execution of a French missionary as justification, and the allies launched a campaign to force China into submission.

The war was brutal but brief. By 1858, British and French troops captured key cities, including Tianjin, and forced the Qing to sign the Treaty of Tianjin, opening more ports, legalizing opium, and granting Westerners extraterritorial rights. The conflict culminated in 1860 with the sacking of Beijing’s Summer Palace, a devastating cultural loss. The treaties deepened China’s subjugation, fueling internal unrest like the Taiping Rebellion and weakening the Qing dynasty, which fell in 1912.

Globally, the war exemplified Western imperialism, with Britain and France exploiting China’s vulnerabilities to expand colonial influence. Socially, it highlighted the opium trade’s devastating impact on Chinese communities, disproportionately affecting the poor. In Ireland, a British colony, the war was followed with interest, as Irish soldiers served in British campaigns, while nationalists drew parallels to their own struggles against imperial rule. The war also raised ethical debates in Britain, with critics like William Gladstone condemning the opium trade’s immorality.

On October 8, 1856, the Second Opium War began, exposing the raw power of colonial ambition and its toll on a proud nation. It was a moment of conquest and tragedy, reshaping China’s trajectory and global trade. Today, we reflect on this conflict, honoring the resilience of those who endured its consequences and the lessons of justice and sovereignty it imparts.

Published by The Uncharted Past Team

On This Day in History: October 7, 1959 – Luna 3 Photographs the Moon’s Far Side

On This Day in History: October 7, 1959 – Luna 3 Photographs the Moon’s Far Side

On October 7, 1959, the Soviet Union achieved a historic milestone in space exploration when the Luna 3 spacecraft captured the first-ever photographs of the Moon’s far side, a region perpetually hidden from Earth’s view. Launched just two years after Sputnik 1, this triumph of Soviet engineering revealed a previously unseen lunar landscape, advancing scientific knowledge and intensifying the Cold War Space Race. The event not only showcased human ingenuity but also captivated global imagination, leaving a lasting legacy in our quest to explore the cosmos.

Luna 3, an unmanned probe, was launched on October 4, 1959, from the Baikonur Cosmodrome. Equipped with a dual-lens camera, it entered a lunar flyby trajectory, passing 6,200 miles from the Moon’s surface. On October 7, it began photographing the far side, capturing 29 images over 40 minutes using a complex system of film development and radio transmission. The images, though grainy, revealed a rugged terrain with fewer “maria” (dark plains) than the near side, naming features like the Sea of Moscow and Tsiolkovsky Crater. Transmitted to Earth by October 18, the photos were a scientific sensation, offering the first glimpse of the Moon’s hidden half.

The achievement was a propaganda coup for the Soviet Union, led by Nikita Khrushchev, amid fierce competition with the United States. Coming after Luna 2’s Moon impact in 1959, it underscored Soviet technological prowess, spurring NASA to accelerate its programs, culminating in the Apollo landings. Scientifically, Luna 3 reshaped lunar studies, confirming the far side’s distinct geology and fueling theories about lunar formation. Socially, it inspired global awe, with even neutral Ireland following the Space Race through media, reflecting universal fascination with space.

The mission’s impact extended beyond science. It symbolized Cold War rivalry, driving innovation but also military applications, as rocket technology underpinned both exploration and missile development. In Ireland, where scientific education was growing, Luna 3’s success sparked interest in astronomy, with observatories like Dunsink tracking space developments. Globally, it paved the way for future lunar missions and deep-space exploration, influencing everything from satellite technology to science fiction.

On October 7, 1959, Luna 3’s photographs of the Moon’s far side illuminated the unknown, pushing the boundaries of human discovery. It was a moment of scientific triumph and global inspiration, reminding us of our shared curiosity about the universe. Today, we honor this milestone, reflecting on its role in uniting humanity in the pursuit of knowledge beyond our world.

Published by The Uncharted Past Team

On This Day in History: October 6, 1973 – The Yom Kippur War Begins

On This Day in History: October 6, 1973 – The Yom Kippur War Begins

On October 6, 1973, the Middle East erupted into conflict as Egypt and Syria launched a coordinated surprise attack on Israel, initiating the Yom Kippur War. Timed on Yom Kippur, the holiest day in the Jewish calendar, this assault aimed to reclaim territories lost in the 1967 Six-Day War. The war, lasting until October 25, reshaped regional geopolitics, tested Cold War alliances, and left a lasting impact on global diplomacy, energy markets, and peace efforts, with ripples felt even in neutral Ireland.

Egypt, under President Anwar Sadat, and Syria, led by Hafez al-Assad, sought to reverse Israel’s occupation of the Sinai Peninsula and Golan Heights. At 2:00 p.m., Egyptian forces crossed the Suez Canal, breaching Israel’s Bar-Lev Line, while Syrian troops advanced into the Golan. The attack caught Israel off guard, with reservists mobilized slowly due to the holiday. Early Arab gains—Egypt recaptured parts of Sinai, and Syria neared the Sea of Galilee—stunned Israel’s military, which suffered heavy initial losses. However, Israel, under Prime Minister Golda Meir, rallied, launching counteroffensives that encircled Egyptian forces and pushed Syria back by mid-October. A UN-brokered ceasefire ended the war, with about 2,800 Israeli and 15,000–20,000 Arab deaths.

The war’s global impact was profound. The U.S. and Soviet Union, backing Israel and the Arab states respectively, nearly clashed, escalating Cold War tensions. An Arab oil embargo, led by OPEC, spiked global oil prices, triggering an energy crisis that affected economies, including Ireland’s, where fuel shortages hit hard. The war shifted Middle Eastern dynamics, leading to the 1978 Camp David Accords, where Egypt and Israel made peace, though Syria remained hostile. Socially, it highlighted women’s roles, with Meir’s leadership and female soldiers’ contributions challenging gender norms.

In Ireland, a neutral nation, the war sparked debate over Middle East policy and UN peacekeeping, as Irish troops served in the region. The conflict’s economic fallout, via the oil crisis, fueled inflation and hardship in Ireland, resonating with its own struggles for stability during the Troubles. Globally, the war underscored the fragility of peace and the interconnectedness of geopolitics and resources.

On October 6, 1973, the Yom Kippur War began, a clash that tested nations and reshaped alliances. It was a moment of conflict and resilience, reminding us of the high stakes of territorial disputes and the enduring quest for peace. Today, we reflect on the lives lost and the lessons learned, honoring the pursuit of reconciliation in a divided world.

Published by The Uncharted Past Team

On This Day in History: October 5, 1962 – The First James Bond Film Released

On This Day in History: October 5, 1962 – The First James Bond Film Released

On October 5, 1962, the silver screen lit up with the premiere of Dr. No at the London Pavilion, introducing the world to James Bond, the suave British secret agent 007. This inaugural film in the James Bond franchise, based on Ian Fleming’s 1958 novel and starring Sean Connery, launched a cultural phenomenon that redefined cinematic espionage and captivated global audiences. The release of Dr. No not only transformed popular culture but also reflected the Cold War era’s fascination with intrigue, technology, and glamour, leaving an enduring legacy in film and beyond.

Produced by Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman for a modest $1.1 million, Dr. No introduced Bond as a charismatic MI6 operative tasked with investigating the disappearance of a British agent in Jamaica. Directed by Terence Young, the film pitted Bond against the sinister Dr. Julius No, a SPECTRE operative, blending action, exotic locales, and romance—hallmarks of the series. Connery’s portrayal, with his cool demeanor and iconic line, “Bond, James Bond,” set the template for the character. Ursula Andress’s emergence from the sea as Honey Ryder became an iconic cinematic moment, advancing gender dynamics in film, though often critiqued for objectification.

The film’s release came at a tense moment in the Cold War, weeks before the Cuban Missile Crisis, resonating with audiences’ fascination with espionage and global threats. Its success—grossing $59.5 million worldwide—spawned a franchise that, by 2025, includes 25 films and billions in revenue. Dr. No established tropes like gadgetry, villainous lairs, and the signature opening sequence, influencing spy genres and action films. In Ireland, where Connery’s heritage was celebrated, the film’s popularity boosted local cinema culture, with Dublin screenings drawing crowds.

Socially, Dr. No reflected and shaped cultural attitudes, blending post-war optimism with anxieties about global power. It elevated British cinema’s global influence, challenging Hollywood’s dominance, and inspired fashion, music, and even tourism in Jamaica. The franchise’s portrayal of women, while groundbreaking in showcasing strong female characters, sparked debates over sexism, evolving in later films. Globally, Bond became a cultural icon, influencing everything from literature to video games.

On October 5, 1962, the release of Dr. No ignited a cinematic revolution, introducing a character who became synonymous with adventure and sophistication. It was a moment that captured the spirit of its time and continues to thrill audiences. Today, we celebrate James Bond’s debut, reflecting on its cultural impact and the enduring allure of 007’s world of espionage.

Published by The Uncharted Past Team

On This Day in History: October 4, 1927 – Mount Rushmore Carving Begins

On This Day in History: October 4, 1927 – Mount Rushmore Carving Begins

On October 4, 1927, a monumental endeavor began in the Black Hills of South Dakota as sculptor Gutzon Borglum initiated the carving of Mount Rushmore, transforming a granite mountainside into an iconic American landmark. This ambitious project, depicting the faces of presidents George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt, and Abraham Lincoln, became a symbol of national pride and ingenuity. The event, rooted in cultural ambition and regional boosterism, not only reshaped the landscape but also sparked debates over legacy, land rights, and identity, leaving a lasting mark on American history.

The idea for Mount Rushmore originated in 1923 with South Dakota historian Doane Robinson, who sought to boost tourism by creating a grand monument. Borglum, a renowned but controversial sculptor with ties to the Ku Klux Klan, was chosen for his bold vision. On October 4, he began work, using dynamite and jackhammers to carve 60-foot-tall faces into the granite, selected for its durability. The project, funded by private donations and federal support, took 14 years, employed 400 workers, and cost nearly $1 million, completed in 1941 without a single fatality—a remarkable feat given the dangerous conditions.

Mount Rushmore’s cultural significance was profound. The chosen presidents symbolized America’s founding, expansion, progress, and unity, reflecting a narrative of triumph. However, the site, sacred to the Lakota Sioux as the Six Grandfathers, was part of land promised to them by the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie, seized after gold discoveries. The carving sparked protests from Native Americans, highlighting colonial legacies and ongoing land disputes. Socially, the project employed diverse workers, though women’s roles were limited to support tasks, reflecting gender norms of the era.

Globally, Mount Rushmore became a symbol of American ambition, inspiring cultural landmarks and tourism worldwide. In Ireland, where national monuments like the Hill of Tara hold similar significance, the project resonated as a parallel to debates over cultural heritage. The monument’s completion during World War II reinforced its patriotic symbolism, though its legacy remains contested due to its environmental and cultural impacts.

On October 4, 1927, the first blasts at Mount Rushmore began a cultural odyssey, carving a nation’s ideals into stone. It was a moment of artistic and engineering triumph, tempered by questions of justice and memory. Today, we reflect on Mount Rushmore’s enduring presence, honoring its creators while acknowledging the complex histories etched beneath its surface.

Published by The Uncharted Past Team

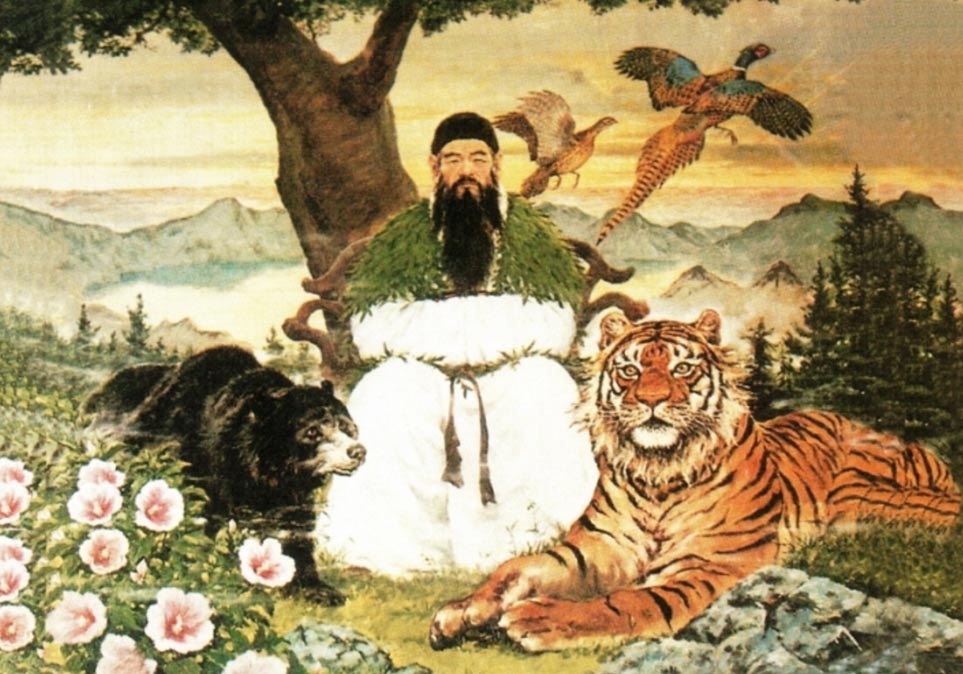

On This Day in History: October 3, 2333 BC – The Founding Myth of Korea

On This Day in History: October 3, 2333 BC – The Founding Myth of Korea

On October 3, 2333 BC, according to legend, Dangun Wanggeom founded Gojoseon, the first Korean kingdom, marking a pivotal moment in Korean cultural identity. This mythical event, enshrined in the Samguk Yusa and Jewang Ungi, recounts how Dangun, born of a divine bear-woman and the heavenly prince Hwanung, established a state centered in Asadal (near modern Pyongyang). While not historically verifiable, this founding myth has profoundly shaped Korea’s national consciousness, fostering a sense of unity and heritage that endures in both North and South Korea, celebrated annually as Gaecheonjeol (National Foundation Day).

The legend, recorded in 13th-century texts, tells of Hwanung descending from heaven to live among humans, teaching them laws and agriculture. A bear and a tiger prayed to become human; Hwanung tasked them with a 100-day trial of eating garlic and mugwort in a cave. The bear persevered, transforming into a woman, Ungnyeo, who married Hwanung and bore Dangun. Dangun, revered as a semi-divine king, is said to have founded Gojoseon, meaning “Ancient Joseon,” uniting tribes and establishing a civilization that laid the groundwork for Korean culture. Archaeological evidence, like Bronze Age artifacts, suggests early organized societies in the region, lending some context to the myth.

The myth’s cultural significance is immense. It symbolizes Korean ethnic unity, with Dangun as the progenitor of the Korean people, and reflects shamanistic and animistic traditions. In South Korea, October 3 is a national holiday, Gaecheonjeol, celebrating national pride and resilience. In North Korea, Dangun’s legacy is tied to state ideology, with claims of his tomb’s discovery near Pyongyang in the 1990s. The myth also influenced Korea’s interactions with neighboring cultures, emphasizing independence amid Chinese and Japanese influences.

Globally, the Dangun myth parallels other origin stories, like Rome’s Romulus, uniting communities through shared ancestry. In Ireland, similar myths, like those of the Tuatha Dé Danann, shaped national identity under foreign rule. The story’s emphasis on a female figure, Ungnyeo, highlights gender roles in early mythology, though women’s agency was limited in historical contexts. Socially, the myth reinforced hierarchical structures but also fostered communal pride.

On October 3, 2333 BC, the mythical founding of Gojoseon by Dangun wove a narrative that continues to bind the Korean people. It is a testament to the power of storytelling in shaping identity and resilience. Today, we honor this cultural milestone, reflecting on how myths forge connections across time, uniting nations in their shared heritage.

Published by The Uncharted Past Team

On This Day in History: October 2, 1980 – Larry Holmes Defends Heavyweight Title

On This Day in History: October 2, 1980 – Larry Holmes Defends Heavyweight Title

On October 2, 1980, the boxing world witnessed a poignant and historic moment at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas, when Larry Holmes defended his WBC heavyweight title against Muhammad Ali in a fight billed as “The Last Hurrah.” This bout, which ended with Holmes’ victory via technical knockout, marked Ali’s final attempt to reclaim the heavyweight crown and signaled a generational shift in boxing. The event transcended sport, reflecting cultural shifts, resilience, and the bittersweet end of an icon’s career, captivating audiences worldwide, including in Ireland.

Larry Holmes, the “Easton Assassin,” held the WBC title since 1978, earning respect as a formidable champion with a devastating jab. Muhammad Ali, at 38, was a global legend, having won the heavyweight title three times and symbolized resistance and charisma. Seeking to become the first four-time heavyweight champion, Ali returned from a brief retirement, despite visible signs of physical decline. The fight, promoted as a clash of titans, drew massive attention, with 24,000 spectators and millions watching on television. Holmes, 31 and in his prime, dominated the bout, landing precise blows while Ali, slowed by age and suspected health issues (later linked to Parkinson’s disease), struggled to respond. After 10 grueling rounds, Ali’s trainer, Angelo Dundee, stopped the fight, marking Ali’s first stoppage loss.

The cultural impact was profound. Ali’s defeat marked the end of an era defined by his charisma, civil rights advocacy, and global influence. Holmes, often overshadowed by Ali’s fame, earned respect but faced criticism for defeating a fading legend. The fight highlighted the physical toll of boxing, raising awareness about athlete health and safety, especially as Ali’s later Parkinson’s diagnosis fueled debates about the sport’s risks. Socially, the event resonated with African-American communities, as both fighters were icons, and Ali’s legacy inspired global figures, including Ireland’s boxing enthusiasts, where the sport thrived.

In Ireland, Ali’s 1972 fight in Dublin had cemented his status as a beloved figure, and the 1980 bout was widely followed, reflecting the country’s passion for boxing. Globally, the fight underscored the sport’s ability to unite diverse audiences, while its emotional weight—Ali’s courage in defeat—left a lasting mark on popular culture, influencing films, music, and literature.

On October 2, 1980, Larry Holmes’ victory over Muhammad Ali closed a chapter in boxing history, blending triumph with the poignant decline of a legend. It was a moment that captured the heart of a sport and its cultural power. Today, we honor the resilience of both fighters, reflecting on their contributions to sport and society’s enduring fascination with their legacies.

Published by The Uncharted Past Team

On This Day in History: October 1, 1553 – Mary I Crowned Queen of England

On This Day in History: October 1, 1553 – Mary I Crowned Queen of England

On October 1, 1553, a historic milestone unfolded in Westminster Abbey as Mary Tudor was crowned Mary I, becoming England’s first undisputed queen regnant. This coronation marked a triumphant yet tumultuous moment, as Mary, a devout Catholic, sought to restore England to Catholicism after the Protestant reforms of her father, Henry VIII, and brother, Edward VI. Her reign, the first led by a woman in her own right, broke gender barriers but ignited religious strife, shaping England’s—and Ireland’s—complex history during a pivotal era.

Mary, born in 1516 to Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon, faced a turbulent path to the throne. Declared illegitimate after Henry’s annulment of his marriage to Catherine, she endured political marginalization. Edward VI’s death in 1553 sparked a succession crisis, with the Protestant Lady Jane Grey briefly proclaimed queen. Mary rallied Catholic support, mustered an army, and deposed Jane within days, securing her claim. On October 1, her coronation, attended by nobles and clergy, affirmed her legitimacy. The ceremony, rich with Catholic ritual, signaled her intent to reverse the Reformation, earning her the moniker “Bloody Mary” for later persecutions.

Mary’s reign was defined by her mission to restore Catholicism. She reinstated papal authority, married Philip II of Spain to secure Catholic alliances, and oversaw the execution of nearly 300 Protestants, including Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, for heresy. These burnings, detailed in John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, tarnished her legacy. Her marriage and policies alienated many, and her failure to produce an heir ensured the Protestant succession of her half-sister, Elizabeth I. In Ireland, Mary’s Catholic policies briefly eased anti-Catholic measures, strengthening ties with Gaelic lords, but her reign also saw early plantation efforts, foreshadowing English colonization.

Globally, Mary’s coronation was a landmark for gender, proving a woman could rule with authority, though her conservative policies clashed with emerging Protestant powers. Her reign influenced Ireland’s Catholic resistance, resonating in later rebellions, and inspired women rulers like Elizabeth. Socially, her persecution of Protestants deepened religious divides, shaping England’s identity for centuries.

On October 1, 1553, Mary I’s coronation broke new ground, affirming a woman’s right to rule while igniting a fierce struggle over faith. It was a moment of triumph and division, reflecting the challenges of leadership in a fractured realm. Today, we honor Mary’s complex legacy, reflecting on her courage as England’s first queen regnant and the enduring impact of her reign on history.

Published by The Uncharted Past Team

Interesting story never knew this. Very powerful

💕💕