Historians, prepare to reconsider a pivotal moment in European history! Princeton Historian Peter Paccione’s “The Prussian Constitution of 1850” challenges the long-held notion that the 1848 revolutions were unequivocal failures. Instead, Paccione unveils how this often-neglected document fundamentally transformed Prussia, placing constitutional limits on the monarchy for the first time and establishing an elected parliament. Moving beyond the “Sonderweg” thesis , he argues that Germany’s constitutional development was far more aligned with the European mainstream than commonly believed. If you’re ready to unravel a complex period and redefine your understanding of German history, this article offers a compelling and essential re-evaluation.

The Prussian constitution of 1850

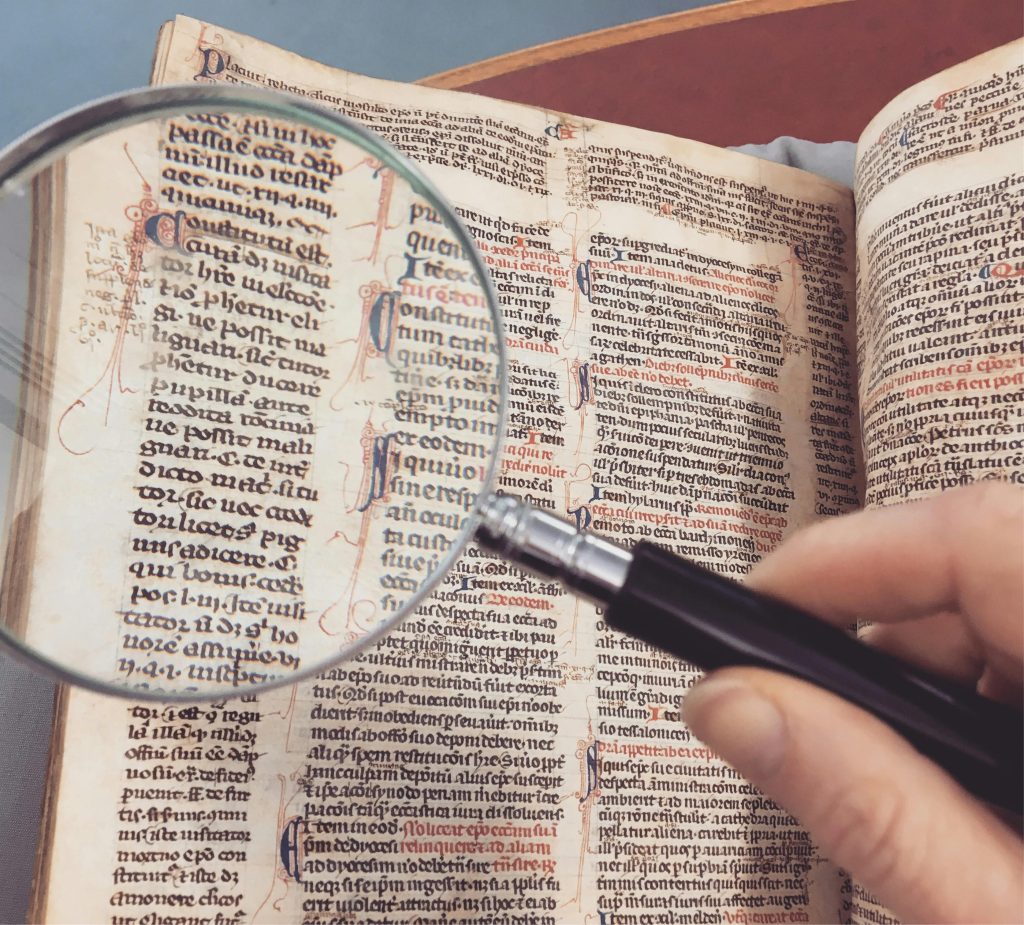

The European revolutions of 1848 have traditionally been considered by historians as failures which ended in reaction. However, in Prussia, revolution resulted in the adoption of a constitution which for the first time placed limits on the monarchy and ended its absolute lawmaking power. The Prussian constitution of 1850 has been neglected by historians, but it was an important document in the constitutional history of Germany. The revolutions of 1848 were not all “failures.”

In May 1848, with the revolution under way, a Prussian National Assembly was elected to ratify a draft constitution which had been written by the liberal government that Frederick William IV had appointed in March. The constitution included such provisions as exclusive royal control over the military and others which the liberal members opposed, and they introduced a counterproposal which would have severely limited royal power. As the debate over the proposed constitution continued, the political winds shifted in the conservatives’ favor and led the king to act. The liberal government was replaced by more conservative ministers; in November, Count Frederick William von Brandenburg was named minister president (prime minister), and martial law was declared. On December 5, the Brandenburg government dissolved the National Assembly and imposed its own constitution.[1] The constitution retained the full executive powers of the monarchy, including its supreme command of the military. It also provided for a bicameral legislature, with a lower house elected by the same democratic franchise which had elected the National Assembly in May 1848, with no property qualification. The upper house was to be elected by men of property who were at least 30 years old.[2]

The constitution of December 1848 would, with much revision, essentially remain in effect until 1918. On May 30, 1849, an election law replaced the universal male suffrage franchise which elected the lower house (the Abgeordnetenhaus, or House of Deputies) of the parliament (Landtag) in the original document with a three-class franchise based upon taxation. Elections were to be indirect. The voters were divided into three classes according to how much taxes they paid. Each of the classes elected one-third of the Wahlmänner (electors) who then elected the 352 deputies. A new parliament was elected in July 1849, and after some additional revision, the constitution was adopted on February 2, 1850. The king swore an oath to the constitution while still maintaining that he ruled by “divine right” and according to the “monarchical principle.” The king possessed sole executive power; ministers were appointed by and were responsible to him alone, he exercised control over foreign and military policy, and he was the supreme commander of the armed forces. The king had the power to summon, prorogue and dissolve parliament, but had to call it at least once a year, in November; he also had the power to issue emergency legislation when parliament was not sitting and to issue executive decrees which implemented legislation. Both houses could initiate legislation, and budgets had to be approved by the lower house. “The most important power the Second Chamber possessed was the power of the purse.” In 1854, after various revisions, the final form of the upper house (the Herrenhaus) was determined to include the nobility, government officials, military officers, and members from such institutions as the church and the universities, appointed by the king.[3] The king had control of the army, but the military would not be left entirely outside the constitution. The minister of war, like the other ministers, was required to countersign any actions which concerned his ministry and defend them in parliament; and the military budget still had to be approved by parliament.[4] Christopher Clark believes that the traditional interpretation of the events of 1848 as a failed revolution is wrong: “…there was no return to the conditions of the pre-March era. Nor should we think of the revolutions as a failure. The Prussian upheavals of 1848 were not, to borrow A. J. P. Taylor’s phrase, ‘a turning point’ where Prussia ‘failed to turn’. They were a watershed between an old world and a new.” Because of the constitution of 1850, “Prussia was now – for the first time in its history – a constitutional state with an elected parliament. This fact in itself created an entirely new point of departure for political developments in the kingdom.”[5] For the first time, the monarchy would not possess the supreme legislative prerogative.

The constitutional crisis of the 1860s was a supreme test of the new Prussian political system. In February 1860, the government introduced an army reform bill which included the expansion of the army from 150,000 to 220,000 men, along with a military finance bill. The regent, Prince William, believed that reforming the army was entirely within the royal prerogative and did not need parliamentary sanction, but he did need parliamentary consent to finance the reform. In May, parliament passed the finance bill as a provisional measure after government assurances that the reforms could be reversed; the reform bill was not passed, but the government still continued to implement the reforms anyway. From 1862 to 1866, parliament, which had a liberal majority, repeatedly rejected the budgets sent to it by the government, which spent money without parliamentary consent. In September 1862, Otto von Bismarck took office as prime minister and put forward the “gap theory” (Lückentheorie), which postulated that the failure of the constitution to anticipate disagreement between crown and parliament caused a constitutional “gap.” In the event of such disagreement, the government was obligated to continue to function without parliamentary sanction, including taxation and spending, but it also had to seek retroactive approval of its actions from parliament when the crisis was over.[6] The crisis was resolved when, in the elections of July 1866, the liberal majority in the lower house was reduced when the conservatives increased their seats from 35 to 136. Bismarck’s foreign policy successes were beginning to shift the political momentum to his side. In August, Bismarck introduced an indemnity bill which retroactively sanctioned the nonparliamentary spending of the government since 1862, which parliament passed.[7] Clark writes that the indemnity bill was an acknowledgement from the government that its actions during the crisis were illegal and was a reaffirmation of the authority of parliament.[8]

Peter H. Wilson disagrees with the traditional interpretation of German political and military history. Prussia, he writes, “did not possess a unique genius for war.”[9] Wilson writes that the course of German history was not a Sonderweg, an aberration from the history of the Western powers. “German history should not be read backwards from [the Nazi period] as a teleologically ‘Special Path’ deviating from a civilized norm, since that contrast between Germany and its Western European neighbors rests on an equally simplistic interpretation of those countries’ history.”[10] I agree that German history did not follow a Sonderweg and I reject the idea that Germany was more absolutist and less constitutionalist than other European powers. In addition to the tradition of Prussian absolutism, Germany possessed another, older tradition, that of representative government. In the early modern period, the other states of the Holy Roman Empire had in common with Brandenburg princes who shared their authority with territorial estates which had the power to consent to taxation. Germany had a heritage of medieval and early modern constitutionalism as rich as anywhere in Europe. In some states, like Brandenburg and East Prussia, the estates lost their power; in others, like Bavaria, Württemberg, Baden, and Saxony, they managed to retain their functions and survived, albeit in a truncated form in some states, until the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The German estates, including Prussia, followed the pattern of development that was taken by most of the representative institutions of Western Europe: they had originated in the medieval period, had gained strength in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, and were weakened or went into abeyance in the seventeenth century with the rise of absolutism. In Prussia, the nobility continued to be politically powerful after the estates ceased to meet and exercised their control over local government. In 1850, Prussia adopted a constitution under which the monarchy ceased to exercise its absolute legislative authority and shared it with a representative institution. Thus, the constitutional development of the German states was within the European mainstream. Beginning with Nassau in 1814, several western and southern states adopted the first German constitutions in the early nineteenth century. In 1850, they were joined by Prussia. Because of the path taken by Prussia which resulted in the formation of a military-bureaucratic state, the adoption of a constitution occurred there later than the other states, and the 1850 constitution gave Prussia a stronger monarchy and a weaker legislature than the other states. The constitution of 1850 was a very conservative document. It preserved many of the traditional prerogatives of the monarchy and established a legislature which was weak and elected by a limited franchise. However, it ended the supreme legislative prerogative of the monarchy and established modern representative government in Prussia.

References:

[1] Christopher Clark, Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600-1947 (Cambridge, MA, 2006), 477-481.

[2] H. W. Koch, A Constitutional History of Germany in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries (New York, 1984), 71.

[3] Ibid., 79-82.

[4] Gordon A. Craig, The Politics of the Prussian Army, 1640-1945 (Oxford, 1955), 122-126.

[5] Clark, Iron Kingdom, 501-502.

[6] Koch, Constitutional History of Germany, 90-97.

[7] Ibid., 101-102.

[8] Clark, Iron Kingdom, 544.

[9] Peter H. Wilson, Iron and Blood: A Military History of the German-Speaking Peoples since 1500 (Cambridge, MA, 2023), 751.

[10] Ibid., 753.

Author: