Was the Habsburg monarchy truly the “absolute” state historians have often portrayed? Peter Paccione’s article, “The Austrian Estates and the Habsburg Monarchy,” challenges this long-held view. He uncovers the enduring power and vital role of the Austrian estates, which, unlike their counterparts in France, thrived throughout the early modern period. Dive into this illuminating analysis to discover how these regional assemblies were not only crucial for taxation and loans, but actively shaped the development of one of Europe’s major powers, demonstrating a persistent “prince-estates dualism” that limited the monarch’s authority. If you’ve ever wondered about the true nature of power in early modern European states, this article offers a fresh and compelling perspective.

The Austrian estates and the Habsburg monarchy

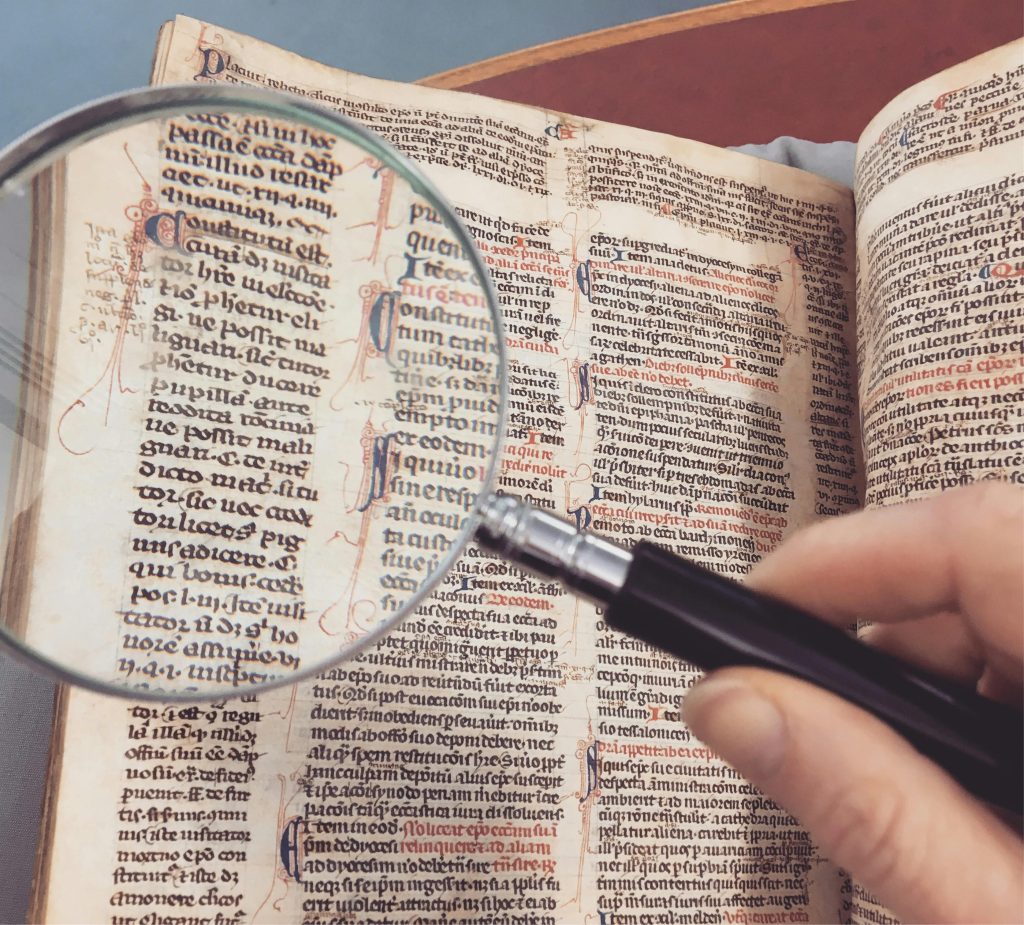

The Habsburg monarchy has been traditionally portrayed by historians as rulers of an “absolute” state. However, this picture needs to be revised. By the early modern period, the Habsburg lands were a composite of provinces each with its own government administration and estates; the government in Vienna exercised direct control over only Lower and Upper Austria.[1] William D. Godsey writes that unlike in France, where the provincial estates had mostly ceased to function except in several peripheral provinces, the Austrian estates “survived in virtually all of the Habsburg monarchy’s central lands, as well as further afield.” Estates met in Lower Austria, Upper Austria, Styria, Carinthia, Carniola, Gorizia, Trieste, Tyrol, Vorarlberg, Breisgau, and Swabian Austria, and in Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia, and the Austrian Netherlands. Hungary had its Diet, as did Transylvania and Croatia.[2] Also unlike in France, where the provincial estates coexisted with parlements and other sovereign courts, in Austria there were no provincial or local corporate bodies like courts to compete with the estates for authority, and Habsburg government offices, including the judicial ones, were not bought and sold and held as private property as they were in France.[3]

The Austrian estates met annually in the Landtage or diets. The Austrian and Bohemian estates were composed of four orders: the clergy (Prätalenstand), the nobility (Herrenstand) the knights (Ritterstand), and the fourth estate, the towns (Vierter Stand). The right to sit in the diets was determined by law and custom. When the diet was not in session, its functions were performed by an estates committee. The Austrian estates were a source of taxes and loans for the Habsburg state. By the eighteenth century, P. G. M. Dickson writes, “estates government was parallel to royal government, and partly overlapped with it.” The main function of the estates was to give consent to taxation, primarily the main tax for the military, the Contribution. The development of a standing army in the seventeenth century increased the dependence of the government on taxation granted by the estates.[4] The Estates of Lower Austria were the most important of the estates because of their location in Vienna and their proximity to the center of Habsburg power. Their meeting place, the Landhaus, was on the square of the Friars Minor almost adjacent to the Hofburg.[5]

During the Thirty Years War, the government was very dependent on the estates for money; in the late seventeenth century, Leopold I (1657-1705) persuaded the estates to increase their monetary support even further.[6] The constant warfare of the late seventeenth century led the government to resort to fiscal expedients to raise money. In 1682, Leopold decreed without the consent of the estates the levying of a property tax, called the “Turk tax,” to pay for the Ottoman war. Leopold based the decree on his sovereign authority as both Holy Roman Emperor and as archduke of Austria, and claimed absolute fiscal power in times of emergency. In 1689, the Austrian estates concluded an agreement, or “recess,” with the government to grant a fixed annual amount for an extended period, in this case twelve years. This would be the first in a series of recesses. In 1690, Leopold enacted the capitation, a direct tax which was to be paid by all subjects of all classes and orders, including the clergy. The capitation was also decreed without the consent of the estates.[7] When Maria Theresa (1740-80) ascended the throne in 1740, the Habsburg financial situation was extremely dire; the government was deep in debt, and the outbreak of the War of the Austrian Succession greatly increased the financial pressure on it. In 1748, to pay for the expansion of the army, the estates agreed to a ten-year recess under which they would grant an annual amount of 14 million florins.[8] Of that, the share of Lower Austria would be 2,008,968 florins annually.[9]

Despite the recesses and other fiscal expedients, the estates continued to be a crucial source of money for the Habsburg state. The recess of 1748 has been traditionally portrayed by historians as a reduction of the power of the Austrian estates and as the final triumph of Habsburg absolutism; the estates were said to be reduced to “ciphers” and “disempowered” and as having experienced “emasculation.” This interpretation has been discredited by recent scholarship. In actuality, the estates continued after 1748 to be instrumental in the governance of the Habsburg lands, especially in finance and taxation. “In fact, the Estates were more essential to the regime than ever.”[10] During the Seven Years War, the estates of Lower Austria became, along with the City Bank of Vienna, the government’s most important source of credit. In July 1756, the Lower Austrian estates lent the government two million florins, followed by another loan of the same amount in September. By 1763, a total of 243,034,687 florins in taxes and loans had been raised by the Austrian, Bohemian, and Hungarian estates. Lower Austria alone raised 43,229,980 florins.[11] Although Joseph II (1780-90) disliked the diets and wanted very much to abolish them, they continued to meet annually and vote taxes during his reign. Joseph had to work with the estates because “formal assent to regular taxation still underwrote the territorial credit systems upon which Habsburg authority continued to rely, just as in Maria Theresa’s day.” The debt in 1780 was larger than it had been in 1763. The Ottoman war of 1788-1790 caused the government to again turn to the estates for loans.[12]

From 1792 to 1815, Austria was almost continuously at war, first against revolutionary France and then Napoleon’s empire. It would be invaded, and Vienna would be occupied twice by Napoleon, in 1805 and 1809. As in previous wars, the government was dependent upon the estates for money, but the unprecedented scope of the Napoleonic wars put enormous pressure on the entire Austrian war machine. The estates adapted to this new situation with changes in their organization; their staffs were greatly expanded to deal with the increased volume of work. The government borrowed so much money that the credit of the estates was almost exhausted by 1805. In addition to the Contribution, new taxes were created, including the property tax known as the Klassensteuer, forced loans, and surcharges. The estates were also involved in supplying and provisioning the army.[13] The estates continued to function during the Metternich era of 1815 to 1848. In the post-Napoleonic period, the Habsburgs respected the role of representative institutions in Austrian governance. Francis II (1792-1835) continued to take part in the ceremony in which he handed his annual tax request to the Lower Austrian estates.[14] Social and economic change after 1815 made the estates system increasingly anachronistic. The government increased its borrowing from the international money markets, lessening its dependence on the estates for money. The upheaval of 1848 set the stage for the end of the estates system, which was abolished by the Stadion constitution of March 1849.[15] According to Michael Hochedlinger, Petr Mat’a, and Thomas Winkelbauer, the Habsburg state had developed a “prince-estates dualism” in fiscal affairs. “In the Habsburg monarchy, the levying of taxes remained dependent on the approval of the individual Landtage until 1848. Even Joseph, who was very critical of the estates, convened state assemblies every year up to 1789 for the purpose of tax approval in the Bohemian and Austrian states.”[16]

Conclusion

I believe that the survival of the Austrian estates demonstrate that the traditional interpretation of the Habsburg monarchy as a “despotism” or as “absolute” is not accurate. The Habsburgs were limited by the estates and were dependent upon them for taxes and loans. The estates also show that European representative institutions did not all decline and cease to function in the early modern period; many, including those in the Habsburg lands, survived and even thrived. In medieval Austria, it was established that while the prince was the supreme judge and lawmaker, he was limited by the rights and privileges of the estates. Among those rights were the rights to grant consent to taxation and military service, consent which was granted in the Landtage. The dualism of prince and estates which was established in the medieval period continued to exist until the nineteenth century. The Austrian estates not only survived, they became instrumental in the development of the Habsburg state into a major European power in the early modern period. Through their right of granting consent to taxation, and through lending money, the estates helped to build the Habsburg military machine. The foundations of this were laid in the medieval period when the estates’ right to give consent to taxation was established.

References:

[1] R. J. W. Evans, The Making of the Habsburg Monarchy, 1550-1700 (Oxford, 1979), 164-165.

[2] William D. Godsey, The Sinews of Habsburg Power: Lower Austria in a Fiscal Military State, 1650-1820 (Oxford, 2018), 29.

[3] Ibid., 38.

[4] P. G. M. Dickson, Finance and Government under Maria Theresia, 1740-1780 (Oxford, 2 vols., 1987), v. 1, 297-301.

[5] Godsey, Sinews of Habsburg Power, 31-32.

[6] Charles W. Ingrao, The Habsburg Monarchy, 1618-1815, second ed. (Cambridge, 2000),60-61.

[7] Godsey, Sinews of Habsburg Power, 127-135.

[8] Dickson, Finance and Government, v. 2, 2-17.

[9] Godsey, The Sinews of Habsburg Power, 206.

[10] Ibid., 213-215.

[11] Ibid., 229-245.

[12] Ibid., 314-316.

[13] Ibid., 359-372.

[14] Ibid., 352-353.

[15] Ibid., 397-398.

[16] Michael Hochedlinger, Petr Mat’a, and Thomas Winkelbauer, Verwaltungsgeschichte der Habsburgermonarchie in der Frühen Neuzeit (Vienna, 2 vols., 2019), vol. 2, 767.

Author: