Whilst the English Civil War and the Stuart monarchy have been extensively studied, the nuances of legal practices under the Commonwealth and Protectorate are sometimes less explored. This analysis, penned by independent researcher Peter Paccione, sheds light on the continuation of established power dynamics and the persistent challenges to individual liberties during this period, revealing the significant, if less heralded, parallels in governance.

Habeas Corpus in the Commonwealth and Protectorate.

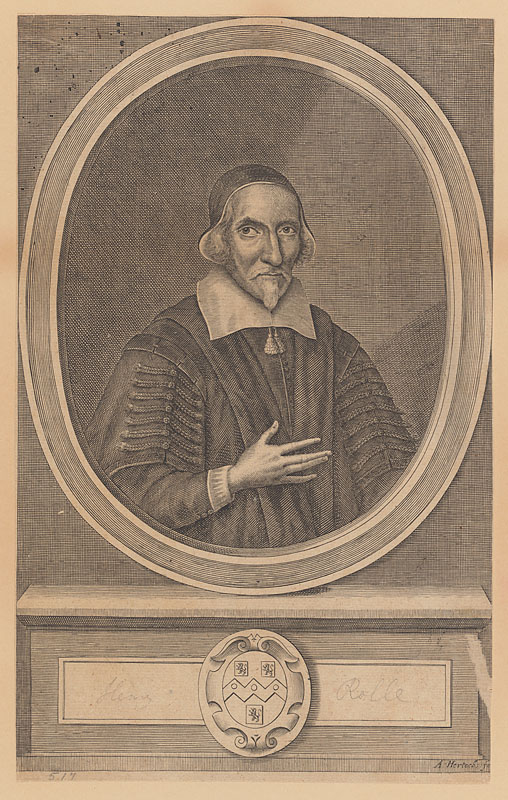

Moving prisoners around to evade justice is nothing new. It was done in early modern England, not only by the Stuart monarchy but also by the government of Parliament during the Civil War and by the Commonwealth and Protectorate. With its assumption of executive powers in 1642, Parliament began to govern in ways that greatly resembled the Stuart monarchy it replaced, often employing methods which circumvented or skirted the law. These included exercising legal powers such as issuing orders of imprisonment against persons. This was resisted by the courts, especially the Court of King’s Bench, which often upheld writs of habeas corpus. In 1649, Henry Rolle was appointed chief justice of the King’s Bench, which was renamed the Upper Bench. Rolle often issued habeas corpus writs. In this, Paul Halliday writes, the government and the courts were continuing the roles they had played under the early Stuarts, with the parliamentary prerogative being exercised in the same way as the royal prerogative had been, and the courts acting to “prevent the worst excesses of novel authority.”[i]

The Commonwealth and Protectorate Parliaments and the Council of State worked together, through people who were members of both bodies. The two bodies exercised executive powers which were much the same as those exercised by the Stuart monarchy and Privy Council, including issuing orders of imprisonment against persons, often using even similar language, as when Parliament ordered imprisonment “during the pleasure of the House.” These orders continued to be contested by the courts, including the Upper Bench, which often upheld habeas corpus writs, but Parliament and the council usually prevailed in these legal conflicts. The orders were defended by the government with the claim that the acts of Parliament and the council were made for reasons of state and were not subject to judicial review. The government often put prisoners physically out of the reach of habeas corpus writs by sending them to remote places like the Channel Islands. Perhaps the most prominent case of this was that of John Lilburne. In 1652, the House of Commons banished Lilburne to the Netherlands for libel against a member of Parliament. Lilburne returned to England in 1653 and was arrested and tried in a London court, where he was acquitted. Parliament rearrested him, put him in the Tower, and told the lieutenant to ignore any habeas corpus writs. When Chief Justice Rolle ordered Lilburne’s release, the government ignored him, then, in March 1654, sent Lilburne to the Isle of Jersey. Lilburne sued, but when Justice Richard Aske issued a habeas corpus writ, Protector Oliver Cromwell ordered the court adjourned. Halliday writes, “Power, not law, had won. Whether in Jersey or the Tower, whether on a literal island or a metaphorical one, the effect was the same: as a matter of practice if not of law, Council and Parliament continued to put prisoners beyond judicial oversight more effectively than Charles I ever had.”[ii]

Another case was that of John Streater, a printer who was arrested in September 1653 for printing seditious pamphlets. Both Parliament and the council ordered his imprisonment, and he sued habeas corpus. In his trial, Streater condemned his imprisonment as violations of the Petition of Right and the Star Chamber Act, but the court upheld Parliament’s imprisonment order on the grounds of parliamentary supremacy. In 1654, after Cromwell’s dissolution of Parliament, Streater sued again, and Rolle ruled that the order was nullified by the dissolution of the Parliament that had issued it. The council sent other prisoners to offshore islands. John Ashburnham, a royalist, was sent to Guernsey three times. Robert Overton was put in the Tower in 1655, then sent to Jersey in 1658 without being charged or tried. John Biddle was arrested in 1655 for blasphemy, and Cromwell ordered him to the Isles of Scilly until the council moved him to a London prison, from which he was freed by a habeas corpus writ.[iii] William Prynne, who had been convicted of seditious libel by the Star Chamber in the 1630s and sent to Jersey by Charles I, said that both the Stuarts and Cromwell put prisoners in “foreign isles…without any legal sentence.” In 1659, Overton was brought from Jersey to the House of Commons, which voted that the warrant for his imprisonment was “illegal and unjust.” After the Restoration, the moving of prisoners to islands continued. Overton was arrested again in 1660 and sent back to Jersey; the political theorist James Harrington was sent to Drake’s Island in Plymouth harbor in 1662.[iv]

Following the dissolution of the first Protectorate Parliament in January 1655, Cromwell and his council became increasingly concerned about the security of the regime against royalist conspirators. This fear, which Barry Coward calls a “siege mentality,” was reinforced by Penruddock’s rising in March. In response, the government resorted to actions which were illegal and extralegal, including the creation of the major general system and the levying of the decimation tax. Another was to establish a central registry office in London to which all royalists visiting the capital were required to report.[v] Cromwell did not hesitate to circumvent Parliament and violate the rule of law in order to ensure the security of the state. David L. Smith writes that the justifications he used for his actions were reminiscent of those used by the early Stuarts to defend the forced loan, ship money, and other measures. Cromwell committed “breaches of the very liberties and privileges that he had fought for in the civil wars.”[vi] This was one aspect of the continuity between the Interregnum governments and the Tudor–Stuart monarchy they replaced; another was the employment of arbitrary methods of governance, particularly in the legal sphere. However, in most areas Cromwell was careful to observe the limits placed upon him by Parliament, especially in matters of finance. He generally did not raise money except through Parliament, including when he needed additional financial aid during the Spanish war of 1656-57, and he submitted accounts of state finance to Parliament. “In his dealings with the legislature, Cromwell only rarely exceeded the powers given him under the constitution, and in practice he generally sought Parliament’s advice and consent where required to do so.”[vii] As Patrick Little and David L. Smith point out, Cromwell never succeeded in establishing an effective working relationship with Parliament. He opened each Parliament optimistic that he would be able to work with them, but he was always disappointed. Cromwell faced opposition in Parliament over several issues, including the constitution, religion, and taxation. Members objected to the wide powers granted to the Protector by the Instrument of Government of 1653 and sought to reduce them. The members opposed Cromwell when he bypassed Parliament and exercised emergency powers, especially the raising of money without their consent, actions which reminded them of the early Stuarts.[viii] Another element of continuity with traditional English governance was the constitutional structure of the Commonwealth and Protectorate. As Alan Cromartie has pointed out, the abolition of the monarchy simply changed the form of the executive, but did not change its substance. The single-person monarchy became the plural executive of the Council of State until the Instrument of Government restored the single executive; “the Rump did not abolish the English monarchy so much as temporarily relocate it.” The Humble Petition and Advice of 1657, with its provision for an upper house and its offer of a crown to Cromwell, “continued the process of creeping Restoration.” The establishment of an upper house and the increasingly monarchical trappings of the office of Lord Protector were signs that the country was reverting to traditional constitutional arrangements after several years of experimentation.[ix]

Conclusion

The exercise of executive power in early modern England largely stayed constant regardless of who was in power, whether it was the Tudors, the Stuarts, Parliament, or Cromwell. It often involved actions which violated the law, such as the imprisonment of persons without charge or trial and the evasion of habeas corpus writs. Governments defended such actions as in the interest of the state and claimed that they could not be reviewed by the courts. This was one of the elements of continuity between the various governments: the Tudors, the early Stuarts, the Commonwealth, the Protectorate, and the later Stuarts all behaved similarly when it came to defending the interests of the state and prosecuting criminals. The leaders of the English Revolution may have opposed the illegal exercise of authority by the Stuarts, but when they came to power they governed in much the same fashion. The Commonwealth and Protectorate were not radical breaks with past governance but were continuations of it. The supposedly revolutionary governments of Parliament and the Commonwealth and Protectorate were very traditional when it came to dealing with the justice system and in many other ways.

Sources used:

[i] Paul D. Halliday, Habeas Corpus: From England to Empire (Cambridge, MA, 2010), 160-165.

[ii] Ibid., 226-228.

[iii] Ibid., 228-229.

[iv] Ibid., 229-231.

[v] Barry Coward, The Cromwellian Protectorate (Manchester, 2002), 51-70.

[vi] David L. Smith, “Oliver Cromwell and the Protectorate Parliaments,” in Patrick Little, ed., The Cromwellian Protectorate (Woodbridge, UK, 2007), 29-30.

[vii] Peter Gaunt, Oliver Cromwell (Malden, MA, 1996), 159.

[viii] Patrick Little and David L. Smith, Parliaments and Politics during the Cromwellian Protectorate (Cambridge, 2007), 132-147.

[ix] Alan Cromartie, The constitutionalist revolution: An essay on the history of England, 1450-1642 (Cambridge, 2006), 273.

Author:

Peter Paccione is an independent researcher specializing in comparative history and the political and constitutional history of Britain and France. He holds a BA in History from the College of Staten Island CUNY and an MA from New York University, and has undertaken graduate study at the University of Virginia. He is also a former staff member of the Princeton University Library.