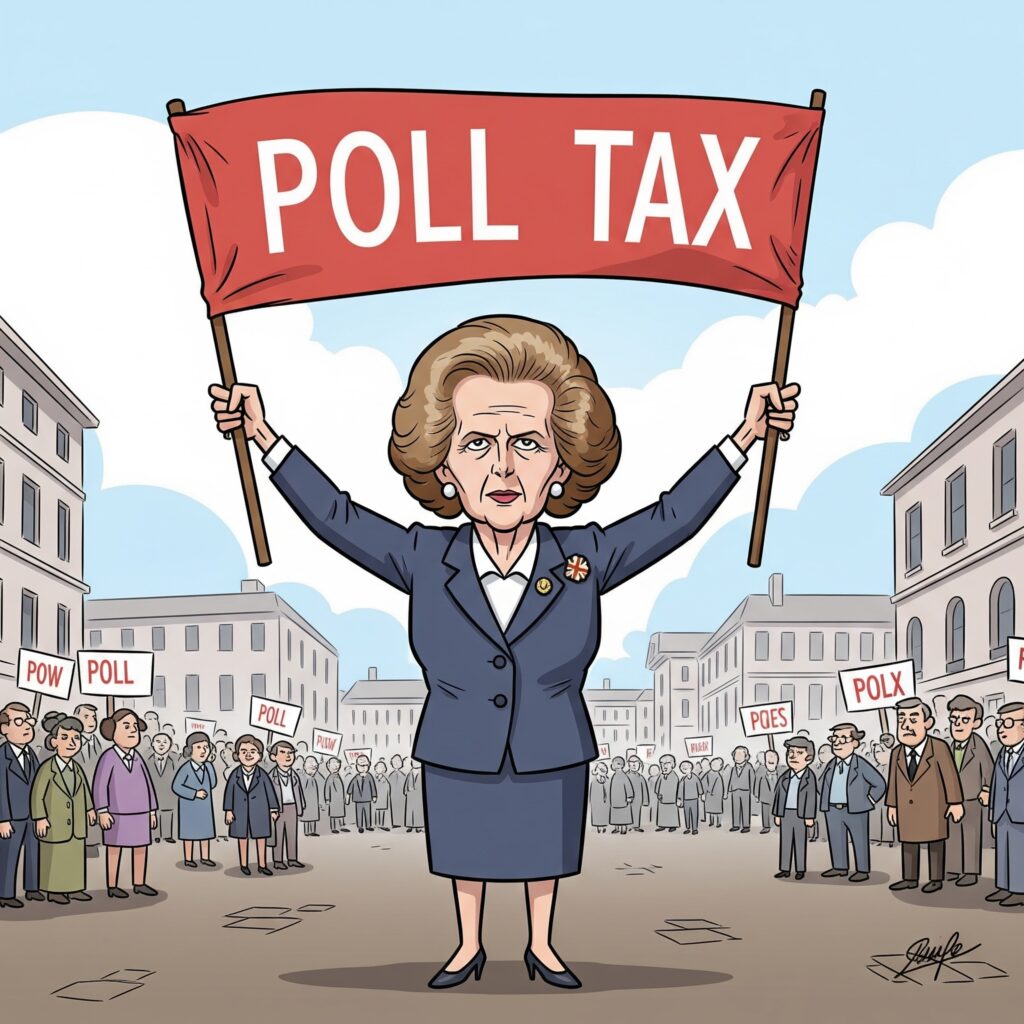

Did you know Margaret Thatcher’s government pitched a poll tax in 1981, only to see it crash and burn before the infamous Community Charge? In this blog post by Peter Farrelly, “The 1981 Green Paper: Thatcher’s First Poll Tax Failure and Its Lessons Ignored,” dive into the explosive mix of skyrocketing rates, political pressure, and practical blunders that derailed this early attempt—yet were shockingly dismissed by 1986. If you’ve ever wondered how a doomed idea resurfaced to shake Britain’s political landscape, Farrelly’s analysis unpacks this critical misstep with gripping clarity.

The 1981 Green Paper: Thatcher’s First Poll Tax Failure and Its Lessons Ignored

In the early 1980s, Britain was a nation grappling with economic turmoil and political upheaval. Margaret Thatcher, the Iron Lady, had swept into power in 1979 with a mandate to reshape a faltering economy and curb the excesses of local government spending. At the heart of her reformist zeal was a burning issue: the domestic rates system, a property-based tax that funded local councils but was widely despised as unfair and outdated. By 1981, her government took a bold step toward addressing this crisis with the Green Paper: Alternatives to Domestic Rates, a document that proposed a radical idea—a poll tax. Yet, this first attempt crashed and burned, dismissed as impractical and unpopular. Shockingly, just a few years later, Thatcher revived the concept, leading to the infamous Community Charge, a policy that would define—and nearly destroy—her premiership. Why did the 1981 Green Paper fail, and why were its lessons ignored? This blog dives into the political drama, economic pressures, and ideological battles that shaped this pivotal moment, revealing a cautionary tale of ambition outpacing pragmatism.

The Rates Crisis: A Ticking Time Bomb

To understand the 1981 Green Paper, we must first grasp the scale of the rates crisis that gripped Britain in the 1970s and early 1980s. Domestic rates were a tax based on the notional rental value of properties, used to fund local services like schools, roads, and waste collection. By the late 1970s, the system was buckling under its own inequities. Rate bills were soaring—households in England and Wales saw an average increase of 13% in 1973, escalating to 30% by 1975–76. In some areas, the hikes were even more staggering, with variations as high as 160% between regions. Businesses, too, were reeling; commercial rates in London jumped by over 300% between 1972 and 1976, prompting warnings from industry leaders like Gerald Lambert of the City Corporation’s Finance Committee that financial firms might flee the capital.

The public’s anger was palpable. In Stockport, over 10,000 residents faced prosecution for non-payment in 1977, a stark symbol of widespread frustration. The rates were seen as regressive, hitting homeowners regardless of income while sparing wealthy renters or large families in council housing. As E.J. Evans noted in Thatcher and Thatcherism, the system was “manifestly unfair,” with tales of pensioners paying the same as affluent households fueling calls for change. For Thatcher, who had long railed against rates—calling them “unjust” in a 1965 speech to her Finchley constituents—the crisis was a chance to deliver on the Conservative Party’s 1974 election pledge to abolish the system within a parliament’s lifetime.

The 1981 Green Paper: A Bold but Risky Proposal

Enter the Green Paper: Alternatives to Domestic Rates, published on December 17, 1981, under the stewardship of Environment Secretary Michael Heseltine. The document was the culmination of nearly a year of research by the Department of the Environment (DoE), driven by mounting political and economic pressures. Conservative Party conferences were dominated by rates-related grievances—82 out of 142 local government resolutions at the 1980 conference focused on the issue. In Scotland, the 1981 Conservative Conference in Perth saw unanimous support for urgent reform, with members demanding either a poll tax or a local income tax to replace rates. Businesses, too, were vocal, with the London Chamber of Commerce warning in September 1981 that spiralling rates were forcing firms to relocate or cut jobs.

The Green Paper proposed four main alternatives to fund the £4.7 billion needed for local government spending: a local income tax, a local sales tax, assigned revenues (shifting costs to central government), and a flat-rate poll tax, estimated at £120 per adult over 18. The poll tax was the most radical, envisioning a per-capita charge that would spread the tax burden across all adults, theoretically enhancing accountability by making everyone pay for local services. Heseltine’s team evaluated these options against seven criteria, including practicality, fairness, accountability, and administrative cost. The poll tax scored well on breadth and visibility but flunked on enforcement and collection costs, deemed too complex and expensive to implement alone.

The Green Paper’s consultation period, spanning three months, revealed a divided response. Some voices, particularly in Scotland, championed the poll tax. The Scottish Young Conservatives, in a survey cited in The Scotsman (April 5, 1982), found 72% dissatisfaction with rates and 55% support for a poll tax, arguing it could replace rates entirely at £117 per head without causing confusion. Sir John Grugeon, leader of Kent County Council, praised its potential to boost accountability, while Professor H.J. McQuade of Tulane University called criticisms “exaggerated,” insisting it was feasible. Yet, the majority leaned elsewhere. A survey of Conservative Party members, including constituency executives and local councils, overwhelmingly favored reforming rates by shifting to capital market values rather than abolishing them. The Convention of Scottish Local Authorities (COSLA) suggested a modest poll tax to supplement reformed rates, proposing a £25 charge. The Association of County Councils echoed this, advocating a hybrid approach.

By June 1982, the verdict was clear. At a ministerial meeting chaired by Home Secretary William Whitelaw, Thatcher endorsed the DoE’s conclusion: no single alternative could replace rates. The poll tax was shelved, and the government pivoted to reforming the existing system, a decision formalized in a July 1983 White Paper. As the White Paper stated, rates were “far from ideal” but “highly perceptible,” “cheap to collect,” and “difficult to evade.” The government promised rate-capping to curb overspending councils and pledged to abolish the Greater London Council, signalling a focus on control rather than revolution.

Why Did the 1981 Green Paper Fail?

The Green Paper’s failure stemmed from a mix of practical, political, and ideological hurdles. Practically, the poll tax’s administrative challenges were daunting. Compiling a register of all adults, tracking mobility, and enforcing payment posed logistical nightmares, especially in a pre-digital era. The estimated costs of collection were deemed prohibitive, outweighing the tax’s theoretical benefits. As the Green Paper itself concluded, a poll tax was “unsuitable” as a sole replacement due to these barriers.

Politically, the proposal lacked broad support. While Scottish Conservatives and some local leaders like Grugeon saw potential, the wider party and local government bodies resisted. Conservative councils, wary of losing autonomy, preferred tweaking rates over adopting a new system. The consultation’s 1,217 responses, though not detailed in the Green Paper’s public summary, underscored this caution, with most favoring incremental change. Thatcher, facing a turbulent first term—marked by 1981’s Brixton riots and a scathing letter from 364 economists condemning her monetarist policies—was in no position to push a divisive reform. Her approval ratings plummeted to 25% in December 1981, per a MORI poll, making bold gambles risky.

Ideologically, the poll tax clashed with Thatcher’s pragmatic side. While she loathed rates, her commitment to fiscal discipline, as outlined in The Downing Street Years, meant she was wary of untested policies that could disrupt her economic agenda. The Green Paper’s other options, like a local income tax, were also unpalatable, requiring 12,000 new Inland Revenue staff and £100 million annually, per the 1976 Layfield Report. With no clear winner, Thatcher opted for the safer path of rate reform, a decision that seemed to close the door on the poll tax.

The Lessons Ignored: A Path to Disaster

Fast-forward to 1986, and the poll tax was back, reborn as the Community Charge in the Green Paper Paying for Local Government. Why did Thatcher ignore the 1981 failure? The answer lies in a perfect storm of political desperation, ideological fervour, and a new cast of policy architects. The 1985 Scottish Revaluation, which saw rate hikes as high as 70% in Perth and Kinross, reignited the crisis. Conservative support in Scotland tanked to 22% by May 1985, per MORI, with party chairman James Goold warning of electoral oblivion. This crisis, detailed in A. Adonis et al.’s Failure in British Government, pushed ministers like George Younger and Malcolm Rifkind to demand drastic action.

Enter Kenneth Baker and William Waldegrave, who led a 1984 task force that revived the poll tax. Their vision, backed by think tanks like the Adam Smith Institute and MPs like Michael Forsyth, framed the tax as a neoliberal dream—simple, accountable, and a weapon against left-wing councils. As Simon Hannah argues in Can’t Pay, Won’t Pay, the tax was “the pinnacle of the Thatcherite programme,” designed to embed individualism and market discipline. By 1987, under Environment Secretary Nicholas Ridley, the policy was rushed through, with Scotland set to implement it in 1989, a year before England and Wales.

The 1981 lessons—administrative complexity, lack of support, and political risk—were swept aside. The task force downplayed enforcement challenges, proposing to piggyback on electoral registers. Consultation feedback, which had sunk the 1981 proposal, was side-lined; Ridley slashed the transitional period to three years, ignoring calls for caution. Thatcher’s own resolve, as she later wrote in The Downing Street Years, was fuelled by a belief that rates were “inherently unfair,” blinding her to the tax’s flaws. As E.H.H. Green notes in Thatcher, the poll tax became a “Tory dream that became a nightmare,” alienating voters and party allies alike.

A Cautionary Tale for Today

The 1981 Green Paper’s failure was a warning Thatcher ignored at her peril. Its rejection highlighted the dangers of a tax that burdened the poor disproportionately, required vast administrative overhaul, and lacked political buy-in. Yet, the Community Charge repeated these mistakes, costing £1.5 billion in setup fees, sparking the 1990 Trafalgar Square riots, and contributing to Thatcher’s downfall, as M. Ricketts observes, signaling she had “lost her feel for what was politically attainable.” The tax’s collapse paved the way for the Council Tax in 1991, a return to property-based taxation that addressed some—but not all—of the rates’ flaws.

What can we learn from this saga? First, radical reforms need broad consensus, not just ideological zeal. Second, ignoring practical barriers, like enforcement costs, courts disaster. Third, policies that exacerbate inequality—Patricia Morgan called the poll tax “one of the most anti-family measures”—risk public revolt. Today, as governments worldwide grapple with tax reform, from wealth taxes to digital levies, the 1981 Green Paper stands as a reminder: ambition must be tempered by feasibility, or the price is political ruin.

What do you think? Could a poll tax ever work in a modern context, or is it doomed to repeat history’s failures? Share your thoughts below!

Author: